At Manhattan Psychology Group, we love working with kids. And we think we’re pretty good at it! But to do right by them and be effective in a treatment program, we usually find we need to work with their parents as our partners. Parents are essential for maintaining the consistency and continuity that is necessary for applied behavior analysis to be successful. But it only works if parents are committed, engaged, informed, and trained. Parent training and participation is thus a key priority of an applied behavior analysis services program at Manhattan Psychology Group. Keep reading to see why.

At Manhattan Psychology Group, we love working with kids. And we think we’re pretty good at it! But to do right by them and be effective in a treatment program, we usually find we need to work with their parents as our partners. Parents are essential for maintaining the consistency and continuity that is necessary for applied behavior analysis to be successful. But it only works if parents are committed, engaged, informed, and trained. Parent training and participation is thus a key priority of an applied behavior analysis services program at Manhattan Psychology Group. Keep reading to see why.

With ABA, Consistency is Key

In the Applied Behavioral Analysis practice at Manhattan Psychology Group, our Board-Certified therapists specialize in working directly with children of all ages and difficulties. And we do so in their full range of natural settings—home, school, camp, and the ice cream shops and subway stops in between. This clinical work is the core of what we were all trained to do, and it is the active heart of our therapeutic approach.

Applied behavioral analysis isn’t, though, about changing behavior when a clinician is present. The goal of therapy is functional: to create adaptive behaviors that generalize across all settings, so the child is truly set up for success. This is the main reason why our clinical work takes place in the normal places of a child’s life, rather than in a removed room in some therapists stuffy office. Another way of saying this is that applied behavior analysis, as a program, requires consistency: children need to learn that the same behavioral rules apply whether they are at home or at school, and practicing behavior across settings helps form habits, making generalization more likely.

Being consistent, however, is hard. A child with a broad suite of services will often have overlapping needs involving multiple types of clinicians, including Speech Language pathologists and occupational therapists that don’t specialize in applied behavior analysis and have different day to day focuses. (It is for this reason that, at Manhattan Psychology Group, our ABA therapists organize and lead teams of clinicians that work together and meet regularly—so that all clinicians are on the same page and can support and reinforce each others’ goals and work.) Moreover, the portion of a week for which an Applied Behavior Analyst is present invariably comprises just a fraction of an overall week. 20 hours per week of Applied Behavior Analyst services is, in relative terms, a fairly intense course of therapy. But a 7-day week with 24 hours per day has 168 hours; even allowing 8 hours per day of sleeping, a “waking” week has 112 hours. 20 hours of Applied Behavior Analyst Services comprises less than 20% of the overall waking hours in a week.

Consistency means parents

The bottom line of all of this is that applied behavioral analysis requires consistency across settings, people, and times of day to be truly effective. And when it comes to consistency and follow-through, the most important actors are parents. Parents are the people most frequently present with their children. Parents are the one the child is most attached to, and to whom the child’s previous behaviors are thus far adapted to. Simply put, parent commitment and ability to follow through can make or break the consistency that an Applied Behavior Analysis program requires for the generalization that is the measure of a program’s success.

Not sure why it works? Let’s first consider Benjamin. Ben is a 5-year-old child with autism spectrum disorder. He won’t sleep independently and when things don’t go his way, instead of verbalizing his frustration he throws non-preferred items out of the bathroom window. Ben’s parents are exhausted. Ben quickly learns that a different set of rules apply with his parents than with his ABA therapists. Ben’s skills don’t generalize. Ben also begins to backslide in therapy—he takes his ABA therapist less seriously, and if his ABA therapist and his parent are around at the same time, he might regress with programming he had been progressing in knowing that he can get a better response out of his parent.

Now let’s consider Oliver. Oliver is a 4-year-old with autism spectrum disorder and ADHD. He is in therapy principally because he only wants to eat foods that are white and while he is capable of spoken language, he prefers to communicate by barking. Oliver’s parents are deeply involved. They learn the strategies the ABA therapist utilizes and replicate them when his therapist is not there. When Oliver eats a green food with his therapist, he will eat the same food with his parents the next day. Oliver learns that using words is a more effective way to get a snack then barking. Oliver makes progress at a faster rate with his therapist because he knows his old tricks will not be effective.

It’s not easy to be an “Oliver’s mom,” and daily life can make it really tempting to be a “Benjamin’s dad.” After all, it is simply easier after coming home from work, when you haven’t seen your child all day, to do what feels convenient, comfortable, relaxing, and good. But the benefits for Oliver, and his parents, are substantial. They’re playing the long game, and it’s going to pay off.

Parent Training at MPG

Because engaged parents are so important to successful outcomes, parent training is a key part of any comprehensive ABA program at Manhattan Psychology Group. What parent training looks like can vary a great deal based on the needs of the child, the parents’ availability and interest, and everyone’s personality. But, in general, our therapists will host at-home sessions with parents in which they teach, model, and role play, and give feedback to parents afterwards. It’s kind of like the therapist is the parents’ coach.

Sessions aren’t everything, of course. To be effective partners in an ABA program, parents need to have a complete understanding of the program and its goals. So, we include parents in our weekly team meetings and, not only that, we take seriously their feedback and listen to what they have to say. It is common to text and/or email throughout the week, as we work as partners to meet the child’s needs.

Many are often surprised when they hear that I work with children as young as 12-months-old. “Why would a 12-month-old ever need therapy?” they often ask. To this question I reply, “Some toddlers have what we call ‘big emotions’ that they end up expressing in unhelpful ways such as extreme tantrums, whining, screaming or aggression. These behaviors can be very frustrating for parents and can lead to more significant emotional and behavioral issues for the child down the road. So, it is best that parents start treatment early in order to change the trajectory and establish a positive relationship between themselves and their child.”

Many are often surprised when they hear that I work with children as young as 12-months-old. “Why would a 12-month-old ever need therapy?” they often ask. To this question I reply, “Some toddlers have what we call ‘big emotions’ that they end up expressing in unhelpful ways such as extreme tantrums, whining, screaming or aggression. These behaviors can be very frustrating for parents and can lead to more significant emotional and behavioral issues for the child down the road. So, it is best that parents start treatment early in order to change the trajectory and establish a positive relationship between themselves and their child.”

Even with this answer though, it can be difficult for someone to imagine bringing a toddler in for mental health treatment. It can be difficult to acknowledge that a child this young needs additional support and therefore a lot of parents decide to wait to engage in treatment with the hopes that things will “work themselves out.” Although through maturation some children may move away from these challenging behaviors, there are many for which these patterns of emotional and behavioral dysregulation persist. Therefore, the research completed thus far shows that the positive outcomes of early intervention, specifically through the implementation of PCIT-T, cannot be overlooked.

What is PCIT-T?

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for Toddlers (PCIT-T) is an evidence-based early intervention program for 12-24 month old children and their caregivers. It focuses on increasing emotional regulation and building self-esteem in toddlers through teaching parents supportive and nurturing parenting practices. Parents learn how to effectively soothe their child when they experience a “big emotion” (e.g., crying, whining or yelling due to frustration or anger) and provide positive attention for their positive behaviors. Parenting skills learned not only lead to increased emotional regulation, but also a secure and trusting parent-child relationship, increased compliance and language development, and decreased parental stress.

Why do parents pursue PCIT-T?

According to research, parents who have participated in PCIT-T have specifically sought treatment due to concerns regarding their child’s behavior such as hitting/biting/scratching themselves and others, screaming, and tantrumming. This, in turn, was leading to parental stress and anxiety and therefore creating a parent-child dynamic that was unhelpful for both the child and parent.

As one can guess, the parent-child relationship is the foundation upon which children learn to engage with others. It is also very dynamic in nature wherein a child’s stress, anger, and anxiety often affects the parent’s mood and vice versa. Therefore, when a somewhat negative dynamic is established neither the parent nor the child are feeling “good” and the child is then also learning maladaptive relationship patterns. Because of this, something needs to be changed for everyone’s benefit.

What specifically needs to be changed in the dynamic?

The goal of parent-child treatment modalities is changing the dynamic from one characterized by negativity to one characterized by positivity. In order for this to occur, research has shown that paying specific attention to and rewarding a child’s positive behavior through the use of positive attention needs to occur.

Oftentimes when dealing with a child with “big emotions,” we tend to pay attention the most to the “tough moments” (e.g., the big tantrums, aggression) which ends up reinforcing these maladaptive patterns. So instead, we need to pay specific attention to the “positive moments,” withdraw our attention when they are seeking it in a negative way, and provide consistent nurturing in a systematic way when they are struggling with a “big emotion.”

What does PCIT-T look like?

PCIT-T focuses on teaching parents the aforementioned skills in a very concrete way. It utilizes both teaching and coaching sessions and parents are given weekly feedback on their skill development. Parents are also taught how to support themselves through recognition and validation of their own feelings, utilizing relaxation strategies when encountering stressful moments with their child, and challenging any maladaptive thinking patterns that are leading to a negativistic views of their own parenting effectiveness.

During teaching sessions, parents meet individually with their therapist to learn specific parenting strategies. These sessions are then followed by coaching sessions during which the therapist coaches the parents in using the skills from behind a one-way mirror using an earpiece. This allows parents to receive immediate feedback on their use of learned parenting skills, helps parents to rapidly learn the correct use of skills, and improves skill generalization to outside of the clinic.

PCIT-T can also be provided via telehealth, which allows the therapist to coach the parent in the home environment. This format can be extremely effective in generalization of the skills, as the parent is being coached right where they will be using the skills the most.

What have been the reported outcomes?

Research done on the effects of PCIT-T that have included parental report indicate a variety of benefits of participating in treatment. These benefits include, but are not limited to the following:

Parent Outcomes:

- Increased confidence as a parent

- Parenting skills development – new tools, strategies and techniques for managing challenging behaviors

- Improvement in the parent-child bond

- A better understanding of their own and their child’s feelings, desires, wishes, goals and attitudes

- Decreased parental stress

- Increased emotional availability

Child Outcomes:

- Improvements in overall emotional and behavioral functioning – both with externalizing (e.g., aggression, opposition) and internalizing (e.g., sadness, anxiety, withdrawal) problems

- A secure and stable connection with their parent – which predicts positive social and psychological outcomes across the lifespan

What makes PCIT-T effective?

When parents were asked what elements of PCIT-T they felt were the most helpful, they indicated that they benefited the most from the live coaching and home practice elements of PCIT-T. Regarding the latter, they acknowledged that although consistently practicing the skills at home was difficult, when implemented, it was very effective.

I think we could benefit from PCIT-T. Where can I find more information?

Additional information about PCIT-T at the Manhattan Psychology Group (MPG) can be found at https://manhattanpsychologygroup.com/child-treatment-services/parent-child-interaction-therapy-toddlers-pcit-t-ages-1-2/

References:

Kohlhoff, J., Morgan, S., Briggs, N., Egan, R., & Niec, L. (2020). Parent–child interaction therapy with toddlers in a community‐based setting: Improvements in parenting behavior, emotional availability, child behavior, and attachment. Infant Mental Health Journal, 41(4), 543-562.

Kohlhoff, J., Cibralic, S., & Morgan, S. (2020). A qualitative investigation of consumer experiences of the child directed interaction phase of parent–child interaction therapy with toddlers. Clinical Psychologist, 24(3), 306-314.

Written by Sudha Ramaswamy, PhD, BCBA-D, LBA

Proloquo2Go – Symbol-based AAC and Proloquo2Text

Proloquo2Go is a complete communication solution providing many natural sounding text-to-speech voices, three complete research-based vocabularies, over 10,000 up-to-date symbols, powerful automatic conjugations, advanced word prediction, multi-user support, ease of use and the ability to fully customize vocabularies to meet the needs of individual users from beginning symbolic communication to full literacy. The voices available are a more natural sounding male, female adult or child. The keyboard and picture/text grids can be used for novel sentence building. The images on the buttons are SymbolStix, although the user is able to use real pictures and some pictures are a more life-like cartoon drawing.

Children with Autism:

A visual schedule is a wearable picture-based scheduler designed with children and adults with autism in mind. Using the iPad or iPhone app, a caregiver can make a visual schedule for the wearer. There are icons that are already included and additional icons/photos can be uploaded to the app to make custom icons. The schedule can then be sent to the wearer’s Apple Watch and will alert them when he/she needs to change tasks or start a new task. The app also allows the user to check on what he/she is supposed to be doing at any point in time. Because this is a wearable visual schedule, the user has access to it at all times eliminating the need to keep up with a paper schedule or another device.

Pictello:

This is an easy-to-use application that allows teachers and caregivers to create social stories and schedules with their children. It can be used to recount what you did during the day or weekend by uploading photographs of those particular events. This makes story-telling and recalling information much more powerful and fun with visuals and a voiceover. Pictello makes it easy to create a story step by step. It also makes them much more effective by letting you add realistic details like photos, videos, and audio recordings. The Text to Speech voices included in the app are also helpful if you want to use voiceovers.

Find My Family, Friends & iPhone – Life360 Locator:

This is a wonderful application for children and teens with autism, Family Locator by Life360 is an intuitive tracker app to keep family, friends and caregivers connected. Life360 runs on your mobile device and allows you to view your family members on a map, communicate with them, and receive alerts when your loved ones leave and arrive at home, school or work.

Behaviorsnap:

This is a great application for caregivers and therapists alike. It allows for multiple behaviors to be counted simultaneously within one direct observation. Also four observation types: Interval, Frequency, Duration, ABC. This app is fully customizable for individual children for Frequency, Duration and ABC observations. It also determines frequent triggers and maintaining consequences of problem behaviors. It provides a sophisticated design and meaningful graphs that can be shared in a confidential PDF format.

Choiceworks:

Choiceworks is an application for helping children complete daily routines and tasks, understanding and controlling feelings and to improve their patience. Caregivers, teachers, and therapists use this app with students diagnosed with autism (verbal and non-verbal), ADD, and other learning disabilities to keep them on task and motivated. There are four boards for Schedule, Waiting, Feelings and Feelings Scale. An Image Library is preloaded with over 180 images and audio plus you can add your own images, videos and record your own audio for limitless customizability. One can easily create profiles to personalize and manage multiple users and save an unlimited number of boards for multiple children or different routines.

Validation is one of the most powerful parenting tools, and yet it is often left out of traditional behavioral parent training programs. In general, behavioral parent training programs focus on teaching parents to use positive attending skills, active ignoring for minor misbehaviors and limit setting in a clear and consistent way. While these skills do significantly improve the quality of relationships in the home and help children listen better, they focus less on bolstering emotion regulation skills in children.

Validation is one of the most powerful parenting tools, and yet it is often left out of traditional behavioral parent training programs. In general, behavioral parent training programs focus on teaching parents to use positive attending skills, active ignoring for minor misbehaviors and limit setting in a clear and consistent way. While these skills do significantly improve the quality of relationships in the home and help children listen better, they focus less on bolstering emotion regulation skills in children.

A child’s ability to regulate emotions affects relationships with family and peers, academic achievement, long-term mental health and future success. Parents seeking treatment for behavioral problems often report that their child is overly sensitive or has big emotional reactions compared to siblings or same-aged peers. Indeed, many clinical disorders in children, such as Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), are associated with having more intense emotions and significant difficulty regulating those emotions. Children who experience emotion dysregulation are at increased risk of further mental health problems, including anxiety or depression.

By validating the emotional experience of children, parents can help them learn how to handle the big emotions that often lead to tantrums, meltdowns, and conflict within the family. Helping children learn to self-regulate is one of the most important parenting tasks, as emotion regulation is a critical life skill that is predictive of positive outcomes.

What is validation?

Validation is defined by Oxford Languages as “recognition or affirmation that a person or their feelings or opinions are valid or worthwhile.” When we validate the feelings of others, we put ourselves in their shoes to understand their emotional experience and accept it as real. Validating your child’s feelings does not mean you condone or agree with the actions your child takes. It simply let’s your child know that you understand their feelings and that it’s ok to have those feelings. It gives your child space to express their emotions nonjudgmentally, safely and without ignoring or pushing away those feelings.

How does validation help?

Validation helps de-escalate emotionally-charged situations, while allowing your child to feel heard, understood and accepted. When children are validated, they experience a reduction in the intensity of their emotions. Reducing the intensity of the emotion allows them to move through the meltdown faster and it opens your child up to problem solving or pushing through a difficult situation or task. Your child is better able to decide what to do next, rather than letting the emotion drive the behavioral response.

Validation teaches children to effectively label their own emotions and be more in tune with their body, thereby increasing emotional intelligence. When children can say, “I’m feeling angry” or “I’m so frustrated,” they are better able to effectively communicate their internal experience to the people around them, rather than lashing out with words, acting aggressively or having a tantrum. When they are able to communicate their feelings in this way, the adults around them are more likely to remain calm and offer help. This allows children to feel more accepted and supported, which strengthens relationships and promotes healthy self-esteem and self-worth.

Validation helps children develop frustration tolerance. Many children can become frustrated when working on a difficult or tricky task. When you validate how hard it is, and praise your child for sticking with it, they are more likely to persist.

Lastly, validating children helps them feel more compassion and empathy towards others, which can enhance the quality of their relationships with others.

How we inadvertently invalidate our children

It’s also important to understand how parents inadvertently invalidate their children. Invalidation is when a child’s emotional experience is rejected, judged or ignored. Every parent has unintentionally invalidated the feelings of their child. Many of the things that children get upset about seem trivial to adults or the emotions can seem disproportionate to the situation. It can be hard for an adult to put themselves in a child’s shoes at times.

Parents unintentionally invalidate their children when trying to help calm them. It can be hard to see your child suffering and struggling. Parents sometimes swoop in to reassure their children that everything will be ok. Parents are also too quick to jump to problem solving or suggest a coping strategy. At times, parents want to push the difficult feelings away because it’s hard to tolerate seeing their child in distress. Validation isn’t about fixing problems for our children or trying to change their emotional experience. It’s about allowing your child to sit with their emotion and acknowledge it.

Sometimes children are punished for their emotions or told they are an overreaction. Parents may tell their child to “just calm down,” which only serves to get them even more worked up. Dismissing a child’s emotions as “no reason to be angry” or saying, “you’re acting like a baby,” can make a child feel judged or rejected for their emotional experience, something they often have little control over. When a child is told that their internal emotional experience is wrong over and over, it makes them feel more out of control and less trusting of their own internal experience, which can have lasting negative impacts. It can also damage the relationship between a child and parent.

How can I validate my child?

Validating the emotions of your child can be difficult at times. Often a child’s distress brings on parent distress, and it can be hard to react calmly in the moment. It can also be difficult to ignore the behavioral response of your child. This is especially true when a child is engaging in aggressive or destructive behavior, and in this situation securing safety takes priority. Validation can happen once safety is restored.

Parents can try to validate their child anytime there is a strong emotional reaction to a situation or stimuli. Being present with your child shows them that you support them and their emotions aren’t too big for you to handle. Sitting calmly nearby let’s your child know that you are there and ready to help when they are calm and able to move on. It also models staying calm in difficult situations.

Reflecting back their thoughts or feelings is another way to validate. For example, “It sounds like you were frustrated when your brother knocked your blocks down. I know you worked very hard on building it up.” When children are less able to express their thoughts or feelings, it’s ok for parents to try to guess what they might be feeling. You might say, “I’m guessing your feeling disappointed right now.” It’s also ok to be wrong. It still shows that you are there and trying to understand.

Another way to validate your child is by normalizing their feelings. It can be helpful for children to know they’re not alone and that others would feel the same way. Saying something like, “of course your anxious about starting a new school – everyone feels nervous when starting something new.” Just be sure not to immediately jump in with reassurance at this point. Instead you may say, “it’s ok to feel nervous.”

Validate all feelings even if you don’t agree with the reaction. Try to ignore the behavior and focus only on the emotion. Once your child is calmer, praise their coping or pushing through. For example, “I know that was really hard for you. You were getting very frustrated. I’m proud of you for sticking with it.” Try to anticipate situations that may lead to big emotions and think about how you can validate your child should emotions intensify.

Lastly, don’t forget to validate yourself and model positive coping skills. Kids learn a lot about how to deal with emotions by watching how the adults around them respond to their own emotions. Saying, “I am feeling very frustrated. It makes sense I feel this way, this is tricky. I’m going to take a break and come back to this when I’m calmer.” This models acceptance of emotions, as well as healthy coping, and can go along way in helping children develop emotion regulation skills.

As you know, choosing the right ABA team can be life-changing for a child with ASD and their family. From our experience, the best results come when the team can achieve all 6 of these important goals: understanding the value of continued relationship building with parents, caregivers, and children, appropriate goal setting, treatment consistency, effective communication, meaningful data-tracking (making adjustments as indicated by data) and generalization across settings and providers.

Over the past several years, we have both started new ABA treatment programs with children who have never received quality ABA before, and rescued and revived failed ABA programs with children who were stagnating and/or regressing.

Below is a case example of a revived DOE-funded ABA program by our team from Manhattan Psychology Group (MPG) which showcases the expeditious results we can deliver via our top-level ABA services.

—————————

BACKGROUND

Jessica is a 12 year old female student (information changed for confidentiality) at a self contained, Autism Spectrum Disorder-focused year round school. She presents with global delays in all areas of functioning. Jessica has been receiving ABA services since early 2013; however, the number of hours designated for direct service and parent training, as well as the education levels of therapists have varied widely. At MPG’s first assessment, Jessica showed the most significant skill deficits in the area of functional communication. Specifically, she was unable to make her wants and needs known to others in a consistent or reliable way. At times this resulted in challenging behavior, including aggression, destruction and elopement. Her overall level of functioning was estimated to be that of a 15-month old.

FAILING ABA PROGRAM

When we received the initial referral for this case, Jessica had not received consistent ABA services for about 6 months. This was due to a number of different factors including:

- Poor communication within a team of independent contractors. There was no team leader, communication between providers and parents, consistent data collection or supervision and treatment planning being provided for Jessica and her family. This led to missed opportunities for data collection and a breakdown in treatment consistency between home and school.

- Confusion about licensure standards in New York State. Because the independent contractors were not part of a larger agency that monitored changes in required licensure, many providers were not properly credentialed and therefore unable to provide service within the confines of NYSED law. This created large treatment gaps and regression for Jessica.

- Parental dissatisfaction. Jessica’s parents were increasingly unhappy with a number of providers on the team and unable to resolve the ongoing issues mentioned above. Jessica’s forward progress had been stalled, and again due to the lack of clinical leadership over the independent providers, there was limited communication and no standard for session cancellation or scheduling changes.

OUR ABA TREATMENT PROGRAM

When MPG was referred this case, we immediately jumped into action. Our director of ABA services met with the family, prior therapists, and reviewed records and previous data to assist in initial goal development. We put together a team of licensed behavior analysts and experienced therapists, which included interviewing and hiring 3 of the existing team, letting go of 2 providers and bringing in 2 new providers. All therapists were made employees of MPG, and placed under the supervision of our director of ABA, an experienced licensed psychologist and behavior analyst. We also designated a team leader. Supervision and treatment planning was initiated to ensure ongoing data collection, assessment, and proper evolution of programming. Within two weeks of receiving the referral, our team was in place and ready to start servicing Jessica and her family.

Since February of 2019, we have been providing both school and home/community based services in the following capacity:

- 10 hours per week (2 hours per day) school push in Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA)

- 16 hours per week home based 1:1 ABA

- 4 hours per month ABA supervision

- 4 hours per month Parent Training and Counseling (PCAT).

Building upon the results of the initial skills assessment programs in the following areas were put into place for Jessica: manding (requesting) in varied ways, tacting (labeling) items, functions and prepositions, as well as giving directions (explaining how to do something). Each program is broken down into at least ten different specific program targets, all of which need to be introduced, mastered, and kept in generalization to be reassessed and revisited.

CURRENT STATUS & 6 MONTH OUTCOMES

Jessica mastered 47 program targets between February 2019 and August 2019. The VB-MAPP reassessment completed in August 2019 showed significant progress in the following areas: manding, tacting, listener skills (receptive language), matching, and math. Jessica made tremendous gains in the area of manding, specifically progressing from a 0-18 month range to skills within the 30-48 month range. Her score on the August VB-MAPP was a 134, which places her skills in the 30-48 month range. Overall, Jessica made over two years of developmental growth within 6 months.

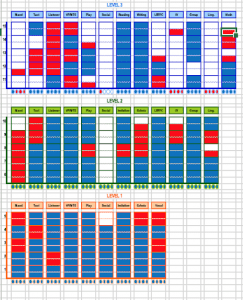

The following visual shows the VB-MAPP skills based assessment, which is conducted every 6 months. Each box designates one developmental skill that is expected of a child within each age range. Moving up from the bottom, skills are designated into the 0-18 month range, 18-30 month range, and 30-48 month range.

The initial assessment (on the left in blue) shows skills mostly centered in the 0-18 month range of functioning (level 1), with functional communication skills (mand) being the lowest. The 6 month assessment (on the right) shows a very large number of additionally mastered skills (in red) centered mostly in 30-48 month range (level 3).

February 2019 August 2019

I look at my schedule and see I have a new patient intake this week. I am going to meet with the parents of a girl in middle school and the brief description in my calendar states that she is experiencing anxiety, trouble sleeping and is looking for “someone to talk to”. I am looking forward to this meeting because intakes represent a new opening and a new opportunity, a new relationship with a client and his or her family and the opportunity to help someone grow, learn more about themselves and start feeling better. The parents are friendly and warm, they say that their daughter has been complaining of anxiety and difficulty sleeping lately, that she sometimes has trouble getting all of her schoolwork done and that she asked if she could talk to someone. In addition to what is happening now that is bringing them to treatment and the history of this problem, we also talk about how their daughter is doing in school, what her friendships are like and what she enjoys doing, what she is like outside of the problems that bring her to therapy. We talk about the parents’ relationship with their daughter, where there is closeness and where there is distance and conflict, and how the problems we are talking about affect the relationship between the parents and their daughter. At the end of the session I have a sense of what I will ask their daughter more about when I meet with her in the next session, what I am curious about and where I believe she needs help. I thank the parents and let them know that we will speak again after I meet with their daughter to give my impressions and talk about the treatment plan going forward.

I look at my schedule and see I have a new patient intake this week. I am going to meet with the parents of a girl in middle school and the brief description in my calendar states that she is experiencing anxiety, trouble sleeping and is looking for “someone to talk to”. I am looking forward to this meeting because intakes represent a new opening and a new opportunity, a new relationship with a client and his or her family and the opportunity to help someone grow, learn more about themselves and start feeling better. The parents are friendly and warm, they say that their daughter has been complaining of anxiety and difficulty sleeping lately, that she sometimes has trouble getting all of her schoolwork done and that she asked if she could talk to someone. In addition to what is happening now that is bringing them to treatment and the history of this problem, we also talk about how their daughter is doing in school, what her friendships are like and what she enjoys doing, what she is like outside of the problems that bring her to therapy. We talk about the parents’ relationship with their daughter, where there is closeness and where there is distance and conflict, and how the problems we are talking about affect the relationship between the parents and their daughter. At the end of the session I have a sense of what I will ask their daughter more about when I meet with her in the next session, what I am curious about and where I believe she needs help. I thank the parents and let them know that we will speak again after I meet with their daughter to give my impressions and talk about the treatment plan going forward.

The following week I meet with the client, her name is *Diana, she is a little bit hesitant at first but opens up and becomes more comfortable as our session progresses. She tells me that she feels anxious about a lot of things, but mostly school and her friends, and that she gets into fights with her parents about her schoolwork because they often catch her on her phone when she is supposed to be doing her homework. She tells me that she goes on her phone a lot because it helps take her mind off of things when she is feeling nervous, and that sometimes she gets so upset that she has no motivation to do her schoolwork and has a hard time focusing on it. She says that it is hard for her to fall asleep at night sometimes because that is often when she has the hardest time controlling her thoughts, and the anxiety makes it hard to fall asleep. We talk more about her feelings of anxiety, when it first started, what else triggers these feelings, what she does to cope when she is upset or anxious. At the end of our session I meet again with her parents to tell them that I believe Diana is struggling with anxiety, and that I believe weekly therapy sessions focused on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), will help Diana to learn the skills and strategies she needs to manage these emotions.

I start treatment with Diana by explaining the connections between thoughts, feelings and actions. We talk about how it’s not possible to simply change how we feel, about how the phrase “stop worrying” never helped anyone, but how we can change our thoughts and what we do, and this can lead to a change in how we feel. We begin by working on some body and sensory based relaxation skills to help Diana calm her body and turn on her relaxation response when she is anxious and stuck in “fight or flight” mode. We come up with a list of triggers and decide what skills will help Diana in different situations. For example, taking deep breaths when she is anxious before a test and using something that is soothing to one of her five senses when she is feeling anxious while studying at home.

We also start talking and learning about Diana’s thoughts. I explain that we all have “automatic thoughts” about many different topics, and that sometimes these thoughts can lead to distressing feelings. Because these thoughts are automatic, we don’t always notice them at first and so Diana starts keeping a thought log, which is a way to increase awareness of and to keep track of her thoughts when she is feeling anxious or upset. We then learn about thought traps, or common ways that people filter their thoughts which lead to negative feelings. For example, when Diana is about to take a test and thinks “I am definitely going to fail”, she is engaging in a thought trap called “predicting the future”, where we predict what will happen based on little or faulty evidence. After Diana has improved at catching her thoughts and identifying what though traps she is getting stuck in, we talk about ways to challenge these negative thoughts by using strategies such as examining the evidence, looking at the probability, defining the terms and creating a spectrum. Based on these thought challenges, we then work on coming up with new, more realistic thoughts that Diana can focus on instead of the original automatic thought.

At first Diana has a hard time filling out the thought log and so we go over in session what she remembers from the week and come up with ways to increase the likelihood that she will fill out the thought log during the following week. We talk about what happened during the week, times that she felt anxious and used her skills, what was helpful and what didn’t work. When Diana comes up with a thought that she has a hard time challenging, we do it together in session. With continued practice, Diana gets better at recognizing her thoughts and challenging them when they occur, and she says this helps reduce her anxiety in the moment.

Diana and I also talk about her relationship with her parents and how it has been more difficult lately. Diana wants to talk with her parents about how she has been feeling because she doesn’t think they truly understand. She is reluctant to tell them on her own so we have a family session where she explains how anxious she has been feeling and how it is affecting her. Diana is nervous to have a session with her parents so we prepare beforehand by going over what she wants to communicate with them during the session. Diana’s parents are open to what she tells them about her experiences with anxiety and how it makes it difficult for her to focus on and complete her schoolwork at times. They want to help Diana to feel calmer and to complete her homework, so we all talk together about ways that they can support Diana such as listening without trying to fix things when Diana tells them about her anxious thoughts and coming up with small rewards that Diana can use to motivate herself when she is struggling to complete her schoolwork. The session goes well and we agree to all check in together again in a few weeks. We continue to have family sessions or parent sessions periodically to talk about how things are going at home.

Diana progresses and feels better able to control and manage her anxiety by using her cognitive and behavioral coping skills. She benefits from having “someone to talk to” and from the support and empathy inherent to the therapeutic relationship. The treatment components of CBT such as relaxation training and thought restructuring, as well as the increased openness and support from the relationship with her parents all lead to Diana’s overall improvement in how she feels.

*Diana is not the real name of a client

Written by Sudha Ramaswamy, PhD, BCBA-D, LBA

What is an ABA Skills Assessment?

An Applied Behavior Analysis Skills (ABA) Assessment is an extremely useful tool in accurately pinpointing the appropriate number of ABA hours (both compensatory and future), the clinically applicable makeup of these hours (direct therapy, therapeutic location, parent training, treatment planning, supervision, etc.), as well as providing a road-map to treatment planning and goal formulation. These assessments measure skills across a wide range of domains-from language, motor imitation, independent play, social and social play, visual perceptual and matching-to-sample, linguistic structure, to group and classroom skills, and early academics, and are most commonly used to assess individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder and other developmental disabilities. These Assessments are not designed to diagnose but rather play a critical role in determining the makeup of ABA support that will provide the best starting off point to make a child whole.

An ABA Skills Assessment conducted as an Independent Evaluation will assess whether a child is progressing in the school district’s program with existing variables in place(e.g., instructional practices, student to staff ratio, staff development opportunities). If progress is not being seen through this evaluation, then changes to the child’s educational program must be contemplated and effectuated. Popular assessments utilized in ABA Skills Assessments include The Assessment of Basic Language and Learning Skills (ABLLS), the Verbal Behavior Milestones Assessment and Placement Program (VB-MAPP), and the Assessment of Functional Living Skills (AFLS) . Although there is no specific licensure required to administer an ABA Skills Assessment, there are several necessary prerequisite skills to conduct the assessment: 1) a comprehensive understanding of Skinner’s (1957) analysis of verbal behavior, 2) knowledge in basic behavior analysis, 3) familiarity with basic linguistic structure; 4) familiarity with the linguistic development of typically developing children, 5) and, have a thorough understanding of autism and other types of developmental disabilities. ABA evaluators typically have master’s or doctoral degree in education, behavior analysis or psychology with a BCBA credential. Typically, the ABA Skills Assessment involves approximately 20 hours of direct testing, observation, interviewing and writing.

What is a Neuropsychological Assessment?

The goal of a neuropsychological evaluation is to comprehensively assess and identify strengths and weaknesses across multiple areas. The evaluation measures such areas as attention, problem solving, memory, language, I.Q., visual-spatial skills, academic skills, and social-emotional functioning. Some children referred for an evaluation may already have a known learning disorder or other diagnosis. Other children may be referred because of a concern or question. The results of a neuropsychological evaluation can help clarify diagnoses related to a range of learning and psychological concerns and develop specific recommendations to address a child’s needs at home and at school. Recommendations for particular therapies and methods as they relate to specific diagnoses stemming from the neuropsychological assessment can also be made. The results and diagnostic conceptualization of a problem—or multiple problem areas—can also assist parents in better understanding their child’s strengths and weaknesses and address related concerns in the home setting. Neuropsychological assessments are administered by neuropsychologists who possess a doctoral degree in psychology, and advanced training in neuropsychology.

What are the similarities and differences between a Neuropsychological Assessment and ABA Skills Assessment?

The goals of the two types of assessments vary. The goal of a neuropsychological evaluation is to assess and identify strengths and weaknesses across multiple areas: intellectual level, language skills, nonverbal or visual skills, memory, attention, organization, judgment, planning, efficiency, academic skills and social/emotional functioning. Neuropsychologists examine how a child’s intellectual ability, learning style, and personality traits interact to affect overall development. A neuropsychological evaluation can help clarify diagnoses related to a range of learning and psychological concerns and develop specific recommendations to address a child’s needs at home and at school. A neuropsychological evaluation will include information about the child’s weaknesses and strengths as a learner and practical recommendations for interventions at school and home will also be offered.

The goal of the ABA Skills Assessment is to provide a representative sample of a child’s existing verbal and related skills repertoire. The assessment contains measurable learning and language milestones that are sequenced and balanced across developmental levels. The skills assessed include mand (requests), tact (labels), echoic (imitation), intraverbal (conversational skills), listener (instruction following), motor imitation (copying), independent play, social and social play, visual perceptual and matching-to-sample, linguistic structure, group and classroom skills, and academics. The ABA Skills Assessment measures specific skills which constitute a designated curriculum. The skills measured are quantifiable and measurable and can be used to document baseline and skill acquisition. The results of the assessment are used to establish priorities and the most effective intervention program. For example, once a child reaches a specific milestone, what’s next? The focus is on establishing a balance among all the skills, establishing their functional use in the natural environment, promoting generative and spontaneous usage of the skills, and verbal and social integration with other children. In addition, a variety of potential IEP goals are presented for each skill area, at each developmental level.

The results of both types of assessments can provide helpful insight into the type of methodology that would best fit the child’s needs and provide professionals, teachers, attorneys and parents or guardians a way to better understand why a child may be having difficulty in specific areas. The evaluations can also provide recommendations for the types of interventions or treatments that may be effective and appropriate, given the child’s specific set of strengths and weaknesses.

How is an ABA Skills Assessment different from a FBA/BIP?

ABA Skills Assessments test overall language level and functioning whereas a Functional Behavior Assessment examines problem behavior(s). A FBA is a process that identifies problem behavior(s), the purpose of the behavior and what factors maintain the behavior that is interfering with the child’s progress. In school, a FBA can be utilized to identify the extent to which a behavior is interfering in educational progress. During a FBA, the behavior analyst conducts baseline observations to collect data on: 1) antecedents, or the environmental prompts leading to the behavior, 2) behavior, or the actions themselves resulting from the antecedents and consequences, the outcome of the behavior that tends to reinforce it. Together, these ”ABCs” of ABA provide the information required to intervene in behavioral problems. An important part of their assessment will start with reviewing previous case history and discussing the child’s behavior with other medical professionals, teachers, family, and caregivers. If previous interventions have occurred, the behavior analyst will study them to gauge their effectiveness and glean any clues from the outcomes.

Hypotheses of the function of behavior based on the FBA then leads to intervention. A behavior analyst will then determine what the child is trying to accomplish through the problem behaviors. Is the child seeking attention? Escape? Sensory stimulation? All the various possible motivations must be analyzed and examined to determine a plan of action that can alter the behavior. If a child yells in class frequently because they are trying to get attention, it requires a different approach than if they are yelling because the work is too challenging. When the functional consequences of the behaviors are understood adequately, the necessary interventions often become obvious, which are then documented in the Behavior Intervention Plan (BIP).

Case Study Example of the Effective Use of an ABA Skills Assessment as an Independent Evaluation

A family argued that their child with autism did not make measurable progress on his IEP goals and that the school failed to address his worsening behavior problems. The parents advocated for an Independent Educational Evaluation that involved an ABA Skills Assessment and Neuropsychological Assessment.

The ABA Skills Assessment revealed:

- Deficits in all of the skill areas tested.

- IEP goals were not appropriate for the deficit areas found on the ABA Skills Assessment.

- Instruction in the classroom did not teach to those specific deficits evidenced through the assessment.

- Evidence-based educational practices were not being utilized in the classroom.

- The staff-student ratio in the classroom did not support the needs of the child.

The Neuropsychological revealed:

- Strengths in visual reasoning and visual-spatial/visual-constructional skills

- Strong rote memory

- Weaknesses in language processing and expression

- Attention and executive functioning challenges

- Reading and writing delays

- Difficulties with self-regulation and social pragmatics

The results of the ABA Skills Assessment were utilized to assess the appropriateness of the child’s IEP goals as they relate to the specific curriculum-based skills tested on the ABA Skills Assessment. The ABA Skills Assessment was also able to offer a comparison of the child’s specific skills with the instruction he was receiving in the classroom and give the evaluator an opportunity to comment on the methods that would best meet the needs of a child with autism.

The results of the Neuropsychological Assessment were utilized to present the child’s overall levels of functioning and how the child’s placement affects the child’s responding. The neuropsychologist was able to observe functioning in the classroom in the following areas: behavioral response to teachers and peers, social interactions with peers, ability to work independently when expected, compliance with adult directives, ability to sustain attention with tasks, and any withdrawal or anxiety in the classroom.

Summary

When working with the family of a child with ASD, there is no better tool in determining educational methodology, duration, intensity and frequency of support. ABA is the gold standard intervention for students with ASD, and therefore must be considered in all cases in which ASD is the primary diagnosis. A licensed behavior analyst (LBA) has achieved the highest level of education available in the field of ABA and through an ABA Skills Assessment, is able to accurately pinpoint both compensatory and future ABA support, including the provision of parent training, location of service, and treatment planning hours.

This pandemic has been hard on families in a lot of ways. Being an employee, a chef, a maid, a home repair expert, a teacher and a parent 24 hours a day 7 days a week is a lot of burden for anyone to bear. Parents who see their children struggling with specific challenges may feel too burnt out to address them heads on right now—and that’s ok. If your children are at home with you, you are already doing an enormous amount to teach them, even if you’re not consciously instructing them.

This pandemic has been hard on families in a lot of ways. Being an employee, a chef, a maid, a home repair expert, a teacher and a parent 24 hours a day 7 days a week is a lot of burden for anyone to bear. Parents who see their children struggling with specific challenges may feel too burnt out to address them heads on right now—and that’s ok. If your children are at home with you, you are already doing an enormous amount to teach them, even if you’re not consciously instructing them.

What is Parent Modeling?

Don’t worry—it doesn’t involve a photo shoot! Clinicians refer to a couple of things when they talk about Parent Modeling. In one case, Parent Modeling is a therapeutic intervention employed by clinicians to teach parents how to change their children’s behaviors, also known as Behavior Skills Training. In the other, Parent Modeling describes what happens when parents behave in a certain way, and their children learn from it. We will focus on this one first. This can be for simple behaviors, like putting dishes in the dishwasher after a meal, or something more nuanced; like reacting to disappointing news. Even when our children are not under lockdown from a global pandemic, parents remain their greatest teachers. Though it may seem like our children are not attending to us, they are constantly absorbing the examples we set, for better or for worse.

How can I use this to improve our lives?

This is a real opportunity to help your children at home. Let’s say your child is sensitive to criticism. You can model how to accept criticism gracefully in your everyday lives. If you want to get creative, you can even conspire with your partner or fellow caregivers to offer extra examples of this to really drive the message home. It could look something like this:

Caregiver 1: Hey honey, I see that you washed the dishes, but I’m noticing there is still some food on them.

Caregiver 2: Thanks for pointing that out, I’ll keep an eye for that next time!

Or

Caregiver 1: How did your presentation go?

Caregiver 2: I worked really hard on it, but my client thought it was lacking in a few areas. I was disappointed, but I’m grateful I have the chance to learn and improve. I’ll do better next time.

Parent modeling can be tricky. Sometimes we may model behaviors we do not want our children to emulate. I’m sure you don’t need me to list examples of occasions where you’ve wanted to tell your child “do as I say, not as I do”. Fortunately, this isn’t all bad. We all make mistakes and do or say things we regret. These are also opportunities to model owning up to our mistakes and moving past them. Maybe you have a child who can’t stop at just one serving of dessert, and you have a sweet tooth too.

Caregiver: Oh man! Those extra cookies seemed like a good idea last night but now my body feels uncomfortable. I wish I had stopped myself. Too many cookies is not a good thing.

Child:…how can there be such a thing as too many cookies?

Caregiver: If we eat so many cookies we make ourselves sick, it can teach our body to start disliking cookies! Also, we won’t enjoy them as much when we are already full, which seems wasteful. I’m going to go exercise and have a salad to make my body feel better—want to join?

If you have a child with special needs or who is working on a skill that is particularly difficult for them to master, you will likely have more success working with a clinician who can provide you with some Behavior Skills Training (BST). This is when a clinician models a behavioral intervention to a parent, and the parent performs the therapeutic intervention. In BST, you are the student, learning through modeling how to therapeutically change your child’s behavior. There are four steps to BST:

Instruction: The clinician will explain to you exactly what you need to do. This is also the time for you to ask questions and get answers that make sense to you.

Modeling: The clinician will show you exactly what to do.

Rehearsal: Your turn! You will practice doing what the clinician described to you and modeled to you.

Feedback: The clinician will provide you with specific information about what you did well and where you can improve. They should use easy to understand terminology and define any behavior terms that you aren’t familiar with. Again, ask questions, and share where you could use some help!

If a behavior you want to elicit is challenging enough to warrant BST, you will likely need to utilize a form of reinforcement to help your child develop the skill. This reinforcement can be faded as the skill becomes easier for your child, but will definitely speed up the learning process. For example, maybe your child absolutely will not wash their hands after using the bathroom. You’ve modeled this to them when you use the bathroom, but for some reason they are not doing this themselves. Well, the first step is to work with their clinician to understand why they won’t wash their hands. Are they bothered by the smell of the soap? Are they afraid they will hear the toilet flush? Once the cause is established, we can make some progress. Let’s say they just don’t want to take the time to do it because they want to get back to playing. Your intervention could look something like this:

Therapist: Ok, Corey doesn’t want to wash his hands because it’s keeping him from his toys. So proactively, you want to reinforce him on his sticker chart for washing his hands. Every time he washes his hands, he gets a sticker, and after 5 stickers he earns staying up 10 minutes past bedtime. Once he does this 5 times in a row he will need 6 stickers, then 7, and we will continue to fade until he doesn’t need it anymore. But reactively (when he doesn’t wash his hands right away after using the bathroom) we want to block his access to preferred activities until they are clean so that he doesn’t learn this is an effective way to get more play time. Does that make sense?

Parent: So…if he doesn’t wash his hands and then he tries to play and then I stop him and make him wash his hands, does he get a sticker?

Therapist: Great question! No. We don’t want to teach Corey that he can have this whole song and dance and attention from you and still earn a sticker. He only gets it when he immediately washes his hands after using the toilet. How about I model it for you?

Parent: Sure.

Therapist: Corey, I see you need to use the bathroom! Don’t forget, you can earn a sticker towards staying up late after you wash your hands! But if you don’t wash your hands you can’t play with anything until you go back and wash them, and you won’t get a sticker.

Ok Parent, now you give it a try.

Parent: Corey, when you use the bathroom if you don’t wash your hands you won’t get a sticker or toys.

Therapist: Great job reminding Corey that there are consequences he won’t like if he doesn’t wash his hands. Let’s not forget that there is also a consequence he will enjoy when he does wash his hands! Corey will be more likely to want to participate if this feels like a positive experience instead of an opportunity for punishment. Lets try again.

The Caregiver and the Therapist will continue to work together until the parent feels confident and comfortable with the procedure—just like you would want your child to feel if you were teaching them a new skill.

Whether you modeling a behavior or you learning to change your child’s behavior from a therapist modeling to you, we are here to help. Please feel free to reach out with any questions on how to best help your child!