A child psychologist explains a trending service: potty training consultations. Here’s what parents need to know about the specialists who are paid to provide guidance, coaching, and support through this milestone.

Young children learn new skills through interactions with their environment. Potty training is one of these skills—it is not innate and needs to be explicitly taught to most young children. Using the bathroom is a major transition for most toddlers who have spent their entire lives going in their diapers, anytime and anywhere. They now not only have to go in a potty, but they also have to identify the urge of having to go, hold ‘it’ in, communicate their need to go, and then make it to the potty in time.

Most potty training methods are grounded in behavioral psychology, which relies heavily on reinforcement to shape new behaviors. This process, called conditioning, is the foundation of most potty training strategies. While some children potty train themselves, most need to be prompted and supported by the adults, mostly parents or guardians, in their lives to fully transition from diapers to underwear.

While some parents find success in choosing a traditional potty training method, many others struggle to implement one consistently. This leaves them frustrated or overwhelmed when the process is harder or takes longer than expected. While most parents would not hesitate to hire a tutor to support their struggling student, they question whether hiring a potty training consultant is appropriate or necessary. But there is no shame in asking and paying for help in parenting when you can afford to.

This is where I come in. I’m a licensed child psychologist who specializes in cognitive and behavioral therapies. While I am not exclusively a professional potty trainer, I am a potty training expert and am often called in to provide consultation and support to families who struggle to potty train their children on their own. Here’s what I want parents to know:

What is a Potty Training Consultant?

Recently, more and more families are beginning to talk about their potty training struggles and are seeking help. Today, many parents are juggling the responsibilities of child-rearing with the pressures of full-time careers. The patience and consistency needed to effectively potty train are often overshadowed by the realities of modern life. Even parents who have the ability may not have the bandwidth to devote the time and resources needed while tending to multiple children or supporting various schedules or activities. Other times, parents have exhausted all their resources and are at their wits’ end. This is when they call in the expert.

A potty training consultant is an individual with extensive experience working with children who are resistant or difficult to potty train. Consultants often have a background in psychology, have received training in behavioral methods to support potty training, or completed a potty training certification course to help support their practice. Potty training consultants help you troubleshoot your potty training obstacles and get your child on the path to success. They work with parents to create a plan that works for them and their child to address issues they may be experiencing.

Potty Training Specialist Cost and Services

Potty training consultants offer a wide array of services from phone consultations to in-home potty training. Suggested services are based on the family’s needs. Phone consultation is usually the stepping stone for parents who are frustrated and overwhelmed with the potty training process and need a little extra hand-holding and support. These parents are either looking for a plan to get started or to troubleshoot and tweak what they are currently doing.

In-home potty training allows for demonstrations and hands-on coaching and support. In-home training is typically provided by the day with one to two days recommended depending on the child’s age and whether potty training has already been introduced. In some cases, a half-day is sufficient and in other cases, such as working with children with special needs, three or more days may be needed. Parents are expected to continue using the techniques and supporting the process after the consultant leaves.

Cost of services range based on where the consultant and family reside and what the fair market value is in that region with phone consultations being the more affordable option. In-home training rates range from $50 to $300 an hour based on total time reserved, the consultant’s credentials, and the specifics of the training case. Consultants may charge additional fees when traveling outside of their region.

Potty Training Consultant Vs. Potty Training Classes

Potty training consultants work one-on-one with your family to meet your specific potty training goals. Potty training schools offer group classes for parents or memberships that help support families throughout the potty training process. Each school offers different classes and levels of support, but like many other group supports, such as SAT prep classes and schools, the one-size-fits-all method to potty training does not actually fit all children.”Like teaching anything else, the approach to potty training should be individualized for each child,” says Samantha Allen, professional potty trainer and a behavioral specialist at NYC Potty Training. “If a child exhibits resistance or anxiety about using the toilet, it’s important to assess the underlying issue to help the child with that specific challenge.” Allen also noted a drawback of training schools: no one wants to poop with an audience.

Should I Hire a Professional Potty Trainer?

“Potty training can be extremely stressful and anxiety-inducing for many parents,” explains Kimberly Walker, pediatric sleep therapist and potty training consultant at Parenting Unlimited. “Often, they feel lost on where and how to start and this confusion transfers to the child creating a chaotic, negative experience for everyone.”

This is why hiring a consultant can be helpful. Potty training specialists help remove any power struggle from the experience. They can also cater services for a child who has special needs and may need alternative training methods implemented. A professional keeps parents involved in the training, without making it all-encompassing for them. That, says Allen, is one of the keys to successful potty training.

Finding a Potty Training Consultant Near You

Outsourcing potty training is more common in metropolitan areas says Lauren Trotter, a mom to a 4-year-old son in Houston, Texas. Trotter did a Google search to find a potty training consultant in her area. “The truth is, I didn’t even know where to start,” she says. “And this may not be the case for every family, but I really felt that potty training fell solely on my already hectic plate of things to do as a working mom; it’s completely unfair.” Perhaps one of the silver linings of the COVID-19 pandemic is the increase in accessibility and the ability to communicate virtually, so Trotter ended up contacting me, a NY-based potty training consultant, for support.

Trotter and I worked together to develop a strategy to train her son. “For me, getting professional help was the best decision I ever made,” says Trotter. “I was expecting to learn a lot from hiring a consultant but what I didn’t realize was how much I needed support, counseling, and the encouragement to hold my son’s daycare, my son, and myself accountable.”

If you are interested in finding a potty training consultant, a great place to start is by searching for professional potty training services in your area on Google. Read more about when to start potty training here.

Francyne Zeltser is a licensed psychologist, certified school psychologist, adjunct professor, and mom of two in New York. Dr. Zeltser promotes a supportive, problem-solving approach where her clients learn adaptive strategies to manage challenges and work toward achieving both short-and-long-term goals. You can connect by email, DoctorZeltser@gmail.com.

Trauma can be difficult to define since each individual experiences and processes life events and trauma differently. Trauma can include abuse, neglect, domestic violence in the family, exposure to substance abuse, or divorce. Children with developmental disabilities are statistically at a higher risk to experiencing trauma than their typically developing peers (Rajamaran et al., 2022).

Trauma can be difficult to define since each individual experiences and processes life events and trauma differently. Trauma can include abuse, neglect, domestic violence in the family, exposure to substance abuse, or divorce. Children with developmental disabilities are statistically at a higher risk to experiencing trauma than their typically developing peers (Rajamaran et al., 2022).

Evidence shows that trauma may impact the physiological and behavioral development of a child (Teicher et al., 2016) and therefore affect one’s response to environmental scenarios. For example, conducting all components of a traditional functional analysis for a child who has experienced neglect would be unethical and harmful (Ramajaran et al., 2022). In other words, imagine not being “informed” or not “assuming” trauma, and thereby placing a child in a room where they are meant to feel alone, for the sole purpose of identifying the function of a given behavior to be automatically reinforcing.

Trauma-Informed Care vs. Trauma-Assumed Care

Trauma-informed care suggests that the provider is aware of trauma experienced by the client, however we aren’t always notified of these events for many potential reasons. Trauma-assumed care is a proactive way of treating our clients, since statistics show that most adults have experienced at least one adverse childhood experience in their lifetime (ACEs; Felitti et al., 1998). We may not be informed of the trauma our clients have experienced during pre-analysis interviews, and it is unlikely that we observe the direct contingencies during these traumatic events. Behavior analysts must know that the impact of trauma has long-term effects on an individual’s psychological and behavioral health, and this should affect the way we teach and treat our clients.

Why is Everyone Talking About Trauma-Assumed Care Now? Recent research is directing behavior analysts to be mindful of their client’s past and to account for trauma when treatment planning and assessing. It is our ethical duty to include TIC in ABA because without doing so, we could be compromising our reputation as behavior analysts, as well as the effectiveness of the treatment we provide (Rajamaran et al., 2022).

A Clarification of Trauma-Assumed Care:

Trauma- assumed care in ABA is a proactive approach to intervention, accounting for the individual’s potential exposure to trauma. It means providing a therapeutic experience that is sensitive to the probability of trauma. This is different from “trauma-specific service,” in which the objective is to directly treat an individual for the trauma that they have experienced (DeCandia et al., 2014). It is our duty to “acknowledge trauma and its potential impact” (Ramajaran et al., 2022) when treating our clients.

Trauma’s Impact on Care

First, it is important that we are aware of where trauma comes from and that we may not ever know about the trauma that a child has experienced. For one, the odds increase that an individual with an intellectual or cognitive disability faces adverse childhood experiences (ACE) in their lifetime (McDonnell et al., 2019). Most of us are treating children on the spectrum or with other disabilities who have experienced trauma, but don’t have a way of describing and communicating that (McDonnell et al., 2019; Ramajaran et al., 2022).

A child engaging in severe or undesired behavior may be “adapting to and coping with past traumatic experiences” (Guarino et al., 2009; Ramajaran et al., 2022). A true behavior analyst understands that stimulus-stimulus pairing could have occurred between a traumatic event and another neutral stimulus. For example, if a child experienced physical abuse,undesirable behaviors could occur in the presence of adults who utilize physical or proximity prompts. (Ramajaran et al., 2002). As another example, it may be insensitive to utilize a response cost system with a child who was in foster care or who has lost a loved one. It’s important to know your learner and their history when assessing and treatment planning to first “do no harm” and to secondly, provide positive meaningful outcomes.

Choice in Trauma-Assumed Care

Secondly, providing an individual with choices has been one evidence-based practice as well as our ethical duty to promote socially valid treatment (BACB, 2020; DeCandia et al., 2014). The professional is providing the individual with a choice to not experience a potentially traumatizing stimulus or event, and instead involves the client in setting their goals, and with making decisions. Hanley (2010) has outlined a few ways to provide choices regarding the procedures and outcomes of an intervention for individuals who are less verbal. One approach includes using a concurrent operant preference assessment. Brower-Breitweisre (2008) gave autistic children the choice to learn through Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) or Treatment and Education of Autistic and Communication Handicapped Children (TEACCH) through a concurrent operant preference assessment. Providing an individual with choices is crucial if we are concerned with one’s quality of life (Martin et al., 2006).

Trauma- Assumed Care and Assent:

In today’s ABA (Hanley, 2019), we worry about the child assenting to the procedures and the outcomes. Hanley instructs all BCBA’s to find the child’s state of happiness, relaxation, and engagement before demands are presented (2019). To acknowledge that trauma has occurred, we respond to noncompliance and aggressions with functional communication training and skill based treatments, by avoiding the overuse of extinction, and by keeping an open door policy so that individuals don’t feel threatened or forced to participate (Hanley, 2019). Trauma-assumed care is televisable, meaning that anyone watching would feel comfortable and sure that the individual in treatment is choosing to be there and is learning skills that improve their quality of life.

The theory that “the student is always right” also means that behavior should inform our decision making with the implementation of interventions (Keller, 1968). A child whose dangerous or maladaptive behavior continues to occur, isn’t learning the necessary replacement skills. Severe behaviors are a sign that there are communication and tolerance skills that are more socially significant than the skills that the child is likely to be avoiding and escaping. When a child is happy, relaxed, and engaged, the child has access to all reinforcers, including attention from adults and tangible reinforcers. Hanley (2019) encourages us to “forget the function” and treat maladaptive behavior as a skill deficit for communication and tolerance. By teaching pivotal skills such as omnibus mands, toleration of transitions and denial of reinforcers, we reveal opportunities for the child to learn in a safe environment (Ward et al., 2020).

References (not complete)

Martin TL, Yu CT, Martin GL, Fazzio D. On Choice, Preference, and Preference for Choice. Behav Anal Today. 2006;7(2):234-241. doi: 10.1037/h0100083. PMID: 23372459; PMCID: PMC3558524.

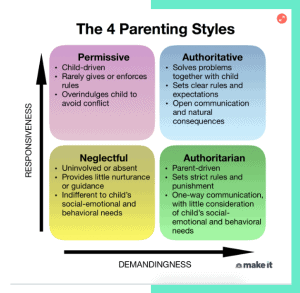

If the question ″What type of parent do I want to be?” has ever crossed your mind, it helps to understand the basics of different parenting styles.

The 4 types of parenting

The four main parenting styles — permissive, authoritative, neglectful and authoritarian — used in child psychology today are based on the work of Diana Baumrind, a developmental psychologist, and Stanford researchers Eleanor Maccoby and John Martin.

Each parenting style has different effects on children’s behavior and can be identified by certain characteristics, as well as degrees of responsiveness (the extent to which parents are warm and sensitive to their children’s needs) and demandingness (the extent of control parents put on their children in an attempt to influence their behavior).

1. The Permissive Parent

Common traits:

- High responsiveness, low demandingness

- Communicates openly and usually lets their kids decide for themselves, rather than giving direction

- Rules and expectations are either not set or rarely enforced

- Typically goes through great lengths to keep their kids happy, sometimes at their own expense

Permissive parents are more likely to take on a friendship role, rather than a parenting role, with their kids. They prefer to avoid conflict and will often acquiesce to their children’s pleas at the first sign of distress. These parents mostly allow their kids to do what they want and offer limited guidance or direction.

2. The Authoritative Parent

Common traits:

- High responsiveness, high demandingness

- Sets clear rules and expectations for their kids while practicing flexibility and understanding

- Communicates frequently; they listen to and take into consideration their children’s thoughts, feelings and opinions

- Allows natural consequences to occur (e.g., kid fails quiz when they didn’t study), but uses those opportunities to help their kids reflect and learn

Authoritative parents are nurturing, supportive and often in tune with their children’s needs. They guide their children through open and honest discussions to teach values and reasoning. Kids who have authoritative parents tend to be self-disciplined and can think for themselves.

3. The Neglectful Parent

Common traits:

- Low responsiveness, low demandingness

- Lets their kids mostly fend for themselves, perhaps because they are indifferent to their needs or are uninvolved/overwhelmed with other things

- Offers little nurturance, guidance and attention

- Often struggles with their own self-esteem issues and has a hard time forming close relationships

Sometimes referred to as uninvolved parenting, this style is exemplified by an overall sense of indifference. Neglectful parents have limited engagement with their children and rarely implement rules. They can also be seen as cold and uncaring — but not always intentionally, as they are often struggling with their own issues.

4. The Authoritarian Parent

Common traits:

- High demandingness, low responsiveness

- Enforces strict rules with little consideration of their kid’s feelings or social-emotional and behavioral needs

- Often says “because I said so” when their kid questions the reasons behind a rule or consequence

- Communication is mostly one-way — from parent to child

This rigid parenting style uses stern discipline, often justified as “tough love.” In attempt to be in full control, authoritarian parents often talk to their children without wanting input or feedback.

What is the best parenting style for you?

Research suggests that authoritative parents are more likely to raise independent, self-reliant and socially competent kids.

While children of authoritative parents are not immune to mental health issues, relationship difficulties, substance abuse, poor self-regulation or low self-esteem, these traits are more commonly seen in children of parents who strictly employ authoritarian, permissive or uninvolved parenting styles.

Of course, when it comes to parenting, there is no “one size fits all.” You don’t need to subscribe to just one type, as there may be times when you have to use a varied parenting approach — but in moderation.

The most successful parents know when to change their style, depending on the situation. An authoritative parent, for example, may want to become more permissive when a child is ill, by continuing to provide warmth and letting go of some control (e.g. “Sure, you can have some ice cream for lunch and dinner.”).

And a permissive parent may be more strict if a child’s safety is at stake, like when crossing a busy street (e.g. “You’re going to hold my hand whether you like it or not.”).

At the end of the day, use your best judgement and remember that the parenting style that works best for your family at that time is the one you should use.

Francyne Zeltser is a child psychologist, school psychologist, adjunct professor and mother of two. She promotes a supportive, problem-solving approach where her patients learn adaptive strategies to manage challenges and work toward achieving both short-term and long-term goals. Her work has been featured in NYMetroParents.com and Parents.com.

Don’t miss:

- A psychotherapist says the most mentally strong kids always do these 7 things—and how parents can teach them

- I raised 2 successful CEOs and a doctor. Here’s one of the biggest mistakes I see parents making

- A psychologist shares the 5 phrases parents should never say to their kids—and what to use instead

When is there consent?

Consent occurs when an individual, typically a parent or guardian, legally permits another individual’s participation. Consent is typically obtained through spoken and written authorization. Assent, on the other hand, is a non-legally binding agreement to participate in an intervention, provided by the client themself. Assent is obtained usually by a child or a dependent adult who cannot make legal decisions for themselves. Acquiring assent from a client may occur in spoken or written communication, but can also differ based on the language and cognitive abilities of that individual.

Why is assent important, if we already are obtaining legal authorization, or consent, from a legal guardian? Behavior Analysts have an ethical duty to acknowledge “…personal choice in service delivery…by providing clients and stakeholders with needed information to make informed choices about services” (BACB, 2020, p.4). Making an effort to obtain assent is how we keep client dignity and provide trauma-assumed care. According to the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects (FPPHS), it is not legally required to obtain assent from children prior to proceeding with interventions (2008). However, according to the Behavior Analyst Certification Board Code of Ethics (BACB), it is our responsibility to treat all individuals equally regardless of disability and age and to “acknowledge that personal choice in service delivery is important” (2020, p. 4). There are a lot of choices that professionals make when designing a behavioral plan. Prioritizing social validity in our practice includes seeking assent when choosing goals, procedures, and the results of the intervention (Wolf, 1978). There are many evidence based approaches for obtaining assent with young children and those with developmental disabilities.

What does assent look like?

Acquiring assent can look differently, depending on the individual one works with. With older children or children with advanced language abilities, one might simply ask the child if they would like to participate. One might also put an agreement in writing for the child, however there are several strategies that can be used with young children or language impaired individuals to acquire assent (Morris, Detrick & Peterson, 2021). Rapport building and instructional fading is one evidence based approach to increase a client’s voluntary participation (Shillingsburg, Hansen, & Wright, 2019). The implementer systematically fades from child-led play to an intensive teaching model across various phases. Instructional fading has shown to decrease problem avoidance maintained behavior, and increase longer durations of time of the child in close proximity to the therapist and in one’s seat without needing many additional resources (2019). In addition, BCBAs may find it simpler to train novice therapists and parents to utilize an instructional fading approach.

Morris et al. (2021) suggests the presentation of choices as another strategy to increase client voluntary participation and thereby accounting for assent. We should “respect and actively promote our client’s self-determination” and acknowledge the importance of our client’s choice during service delivery (BACB, 2020, p. 4). Instead of incorporating aversive interventions such as punishment and extinction to decrease problem behavior, try accounting for the child’s preference by offering choices. McComas (1996) allowed children to choose between emitting a maladaptive response versus utilizing functional communication in order to get access to a reinforcer, such as attention from an adult. By manipulating the duration of time allowed with the reinforcer and the quality of the reinforcer, one can teach children to prefer to use a more adaptive form of communication and to choose against emitting the maladaptive behavioral response. The children were provided access to a preferred stimulus for longer durations when emitting a functional communication response, and less time when emitting maladaptive behavior.

Utilizing concurrent chain procedures is one more way to account for the child’s preference of intervention procedures. By allowing the child to choose the treatment procedures, we are likely to see positive results, lower rates of problem behavior, and our practice remains socially valid. Torellii et al. (2016) conducted preference assessments to assess which topography children preferred when manding. Based on the child’s increased mand responses with the iPad®, it was decided that the child would utilize the iPad® for communication instead of the GoTalk® device. Other studies present how to utilize a concurrent chain procedure to examine client preference to using a microswitch, PECs, sign language, vocal speech and assistive technology device for manding (Winborn, Wacker, Richman, Asmus, & Geier, 2002; Winborn-Kemmerer, Ringdahl, Wacker, & Kitsukawa, 2009). For example, the instructor teaches the child two different mand topographies and then provides simultaneous access to both types of responses. The choice that the child makes when both options are available teaches the instructor which response type is preferred, thereby accounting for assent in procedures and results of the intervention.

How to approach assent and assent withdrawal

How often should we give choices to our clients and how can we account for assent withdrawal? There isn’t a one size fits all response, but it’s better to follow the rule of “the learner is always right” (Keller, 1968). Hanley (2021) encourages choice making and encourages professionals to listen to the child and attend to behaviors, even when we feel like it would be best to ignore those attention seeking behaviors. He also encourages all professionals to keep an open door because “leaving means something is missing or something aversive is present” (2021). By reducing physical behavioral management, and allowing freedom to move and choose where one prefers to be, we are allowing children to consent to the intervention. Rajamaran et al. (2020) gave the ongoing choice for children to either go to the instructional room, a “hangout room” with free access to preferred items and adult attention, or to go home. These children were selected because they exhibited dangerous problem behavior in order to escape or avoid demands and to get access to what they wanted. The results from this study showed that all three children chose to stay and learn important life skills such as functional communication, toleration responses, and contextually appropriate behavior (CAB) (2020) over 90% of the time and did not choose to go home (Rajamaran et al., 2021).

When given a choice between taking a break, or completing work, research has shown that children will choose to work in order to receive a longer or better break than receiving shorter breaks for “free” (Peterson et al., 2005). Children are more likely to stay engaged with a work task without problem behavior when the choice to not work is just as accessible. According to the matching law, individuals will choose to engage in more than one response type, based on the proportion of the reinforcement delivered for each response. Replacing problem behavior that includes partial extinction procedures encourages adaptive behavior through the delivery of higher levels of reinforcement for such positive behavior and lower levels of reinforcement for negative behavior. Many researchers such as Peterson et al. (2005) and Rajamaran et al. (2021) have shown how considering the child’s preference in participation has resulted in a decrease in problem behavior and an increase in children choosing to engage in learning tasks.

References

Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2014). Professional and ethical compliance code for behavior analysts. Littleton, CO: Author.

Keller FS. “Good-bye, teacher…”. J Appl Behav Anal. 1968 Spring;1(1):79-89. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-79. PMID: 16795164; PMCID: PMC1310979.

Morris, C., Detrick, J.J. and Peterson, S.M. (2021), Participant assent in behavior analytic research: Considerations for participants with autism and developmental disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 54: 1300-1316. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.859

Peterson, Stephanie & Caniglia, Cyndi & Royster, Amy & Macfarlane, Emily & Plowman, Kristen & Baird, Sally & Wu, Nadia. (2005). Blending functional communication training and choice making to improve task engagement and decrease problem behaviour. Educational Psychology – EDUC PSYCHOL-UK. 25. 257-274. 10.1080/0144341042000301193.

Rajaraman, A., Hanley, G. P., Gover, H. C., Staubitz, J. L., Staubitz, J. E., Simcoe, K. M., & Metras, R. (2022). Minimizing escalation by treating dangerous problem behavior within an enhanced choice model. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 15(1), 219–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-020-00548-2

Shillingsburg, M. A., Hansen, B., & Wright, M. (2019). Rapport Building and Instructional Fading Prior to Discrete Trial Instruction: Moving From Child-Led Play to Intensive Teaching. Behavior modification, 43(2), 288–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445517751436

Winborn-Kemmerer L, Ringdahl JE, Wacker DP, Kitsukawa K. A demonstration of individual preference for novel mands during functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42:185–189.

Winborn L, Wacker DP, Richman DM, Asmus J, Geier D. Assessment of mand selection for functional communication training packages. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35:295–298.

Wolf MM. Social validity: the case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. J Appl Behav Anal. 1978 Summer;11(2):203-14. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1978.11-203.

As a child psychologist, I speak with so many parents who are concerned about their child’s development or behavior. Mostly my clients aren’t sure what behaviors should raise a red flag for them—”Should I worry when my child does this” or “Is it weird that my child said that…” I’ve heard it all in nearly a decade of working with families.

I’ve even shared those same thoughts: When I became a mom to two boys, Hunter, 3, and Paxton, 1, my work only heightened some of the concerns I, like all parents, have. After all, I witness first hand how parenting can affect kids. Parents have a whirlwind of things to worry about, but we just can’t worry about everything. As long as we love our children and try our hardest to give them a happy childhood, we are doing the best we can.

Here, I share what I’m not worried about when it comes to my kids, and what concerns I prioritize instead. While there’s no right way to parent, it’s possible to feel confident that you’re making the best parenting choices for your little ones.

I Don’t Worry…

If I am being a positive role model

As a working mom, I don’t always get to spend all day with my boys. But what’s more important than the quantity of time you spend with your kids is the quality of the time you do have together. When I am with my children, whether for an hour or a full day, I am responsive to their cues and needs; I provide undivided attention whenever possible to set them up for success. During the work day, my children are with experienced caregivers who help teach them how to be resilient and adaptable to change. Even if you don’t go to work, time apart from you and your partner can help teach your child autonomy and independence. So invite grandma to babysit! A little me-time is healthy for everyone involved.

If they are meeting their milestones

Children meet developmental milestones when they are ready. There are ranges of what is considered appropriate and what may be considered delayed. My colleague Jaclyn Shlisky, Psy.D., mom of Piper, 4, and Harlow, 2, told me that she constantly sees parents comparing their children to others. Her advice: Stop! “Each child learns and grows at his or her own pace,” Dr. Shlisky says. “Focus more on how your children make progress by comparing them to themselves—if they are progressing each day, each week, each month, that’s what really matters. Every day try to find a small win.”

And if you do have concerns, share them with your pediatrician rather than in a mom group on Facebook. Your pediatrician is your expert parenting partner so if you don’t trust your pediatrician, find a new one. Also, don’t worry if a delay is noted. Early intervention services are highly effective. If your pediatrician suggests that you follow up with a specialist or get an evaluation, I recommend doing so immediately. The earlier a problem is identified the more likely the issue can be remediated.

If there’s a change in our routine

Here’s a confession: I keep my children out late on holidays and will sometimes skip a nap to do a fun activity; I’ve even let my kids come into bed with us and watch cartoons on vacation.

So many parents feel they have to stick to a strict schedule or their children will fall apart. There’s no question that children thrive from routine and benefit from clear expectations. Children, like most people, do better when they know what to expect. But changes in your daily routine or schedule will not break your children. Yes, you may have a minor set back or some out of the ordinary behavior as you attempt to get back on schedule. But that is OK. Schedules can be adjusted, sleep can be retrained, and bad behavior can be extinguished, but having ice cream for breakfast on his birthday is something your child will remember forever.

If my kids are picky eaters

As long as the pediatrician doesn’t have concerns about their weight or health, I don’t fight my kids on food. I typically offer two meal choices: what we as a family are eating and what is currently available in my fridge (no complaints here if someone finally eats the leftovers!). If they are hungry they eat, if they aren’t they don’t.

I’ve also seen parents successfully offer a meal with two or more food options. For example, a dinner that consists of a protein, starch, and vegetable should include at least one item that is preferred and another that is new or less preferred. This gives your child a chance to try new foods, but doesn’t force her to eat it. It also guarantees that she will be eating at least part of the meal without protest. I have found that when I try to force my toddler to try something new, he is resistant. However, when I give him the option by putting it on his plate with other familiar and comfortable foods, he is more willing to take a bite since the pressure is low and the choice is his.

If my kids have screen time

Like everything else, exposure to screens and technology can be useful, if it is carefully monitored and regulated by caretakers. Engage with your child while watching TV and discuss the characters and themes of the episode during commercials. Most devices have parental controls—take advantage of them! I love Guided Access on my iPhone, which restricts my son to only using the app that is open and can even shut my phone down after the allotted time is over. Once the phone goes to sleep, he knows it’s time to play with something else. If you have an older child with an iPhone, set up Screen Time, which lets you monitor how they are using their devices and set time limits on app categories like games or social media.

Tablets can also be great educational tools. Many schools have individual iPads for students to use for assignments, and they are often a must-have on long car rides or in waiting rooms. Again, it’s all about how you engage. I’ve had my three-year-old use my phone for a virtual scavenger hunt while sitting in the waiting room for an appointment. I named items that I saw in the room that he would quietly find and photograph them using my phone’s camera. As long as you and your child interact with technology or the screen together, it can be an incredibly valuable tool that you don’t have to fear.

I Do Worry…

About who my kids’ friends are

We go from deciding where our kids sit during circle time to dropping them off at school often without even being allowed to step foot into the building. How will I know if my son is making good friends and can advocate for himself?

Focus your energy toward getting to know your children’s friends and educating your children on how to make good friends. Set up play dates or enroll them in extra-curricular activities and talk to your child after the event about how he thinks it went. It’s OK to suggest things he may want to do differently during the next playdate. For example, if you observed your child never getting to choose the activity, you can say “I noticed that you always agreed to play what Johnny wanted to play, what did you want to play?” Then help provide your child with a script of what he can say or do next time. Role-playing is a great way to help your child develop self-advocacy skills. You can pretend to be the friend or engage siblings in a social role-playing activity.

I also try to encourage my son to do activities that are of high interest to him, as opposed to choosing an activity just because it’s popular. Expose your child to a variety of activities and pursue the ones that your child seems to enjoy. This will teach him to be a leader and not always follow along with the crowd, and he will likely meet peers with similar interests.

If my child is kind

I sometimes observe children acting mean, not because they are actually mean, but because they have heard or witnessed others being mean. Kids are like sponges, they take everything in, even when you don’t think they are paying attention. I always try to teach my children to use kind language like “everyone’s included” and “kindness counts.” I also have honest (age-appropriate) conversations with them about when they observe others being unkind. We discuss what we observed and explore what other options the person had that could have led to more positive outcomes.

Teach empathy: your children do not have to like everyone, but they should still be kind to everyone. Then model this behavior for your children. Invite the whole class to playdates that are held at the local park and greet other families with a smile, even if they don’t reciprocate. When my children and I observe someone being unfriendly we try to evaluate the situation from a different perspective: Is it possible that the person is just having a bad day?

- RELATED: 14 Little Ways to Encourage Kindness

If I am making the right educational decisions for my kids

As educational standards shift, so do societal expectations. So much so that it often feels like our kindergarteners are being prepped more for college readiness than social adjustment. As parents, we are constantly faced with the question of are we doing right by our children. Have we signed them up for enough extracurriculars? Should we enroll them in public or private schools, enrichment or intervention? The options are infinite and the future is unknown.

While I can’t tell you what’s right for your kids, I can confidently say that no decision you make for your children is set in stone. If you think you may be pushing them too hard, try pulling back and see how they do. If you’re unhappy with their school, class, or extracurriculars, call a meeting or make a switch. If your child is struggling and falling behind, request an evaluation. You are your child’s best advocate and the ball is in your court. There is no “one size fits all” to education, so trial and error is your best bet.

If my child is happy

Sure, I know my toddler is happier playing than doing homework but is he really truly happy deep down at his core? This is something that feels so out of my control as a parent. Rather than just worry about it, ask your children directly how she is feeling on a daily basis, and try not to be dismissive of her concerns. It’s important to validate your child’s feelings and show her that you’re here to listen.

It’s also important to realize that while it’s common for a child to be nervous the night before a test, it could be a sign of a bigger issue if your child expresses constant worry about nonspecific causes, is hesitant to engage in activities which would otherwise be perceived as fun, and/or is constantly complaining of physical symptoms (stomachache, headache, etc.) that are not related to medical issues. If this is the case, talk to her about how she feels and try to get to the root of the problem. If there is something bothering her, suggest strategies for her to use. Then follow up with your child on how it went. If your child is still struggling, seek professional help. Low-level issues that are not addressed can turn into larger problems later in life.

Knowing what concerns to prioritize makes the parenting journey much calmer. If you’re feeling worried or stressed, remember you are not the only parent to feel this way. You can turn to your friends, family, or professionals (like a school psychologist or pediatrician) for help.

Francyne Zeltser is a licensed psychologist, certified school psychologist, adjunct professor, and mom of two in New York. Dr. Zeltser promotes a supportive, problem-solving approach where her clients learn adaptive strategies to manage challenges and work toward achieving both short-and-long-term goals. You can connect on email, DoctorZeltser@gmail.com.

Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA) emerges as a potent non-pharmaceutical intervention for children grappling with Attention Deficit Disorder/Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADD/ADHD).

As more parents seek alternatives or complements to stimulant medications, ABA gains recognition for its role in treating these conditions. However, it remains relatively unfamiliar to parents navigating uncertain diagnoses or seeking alternatives to pharmaceuticals. A behaviorally trained psychologist or a Board Certified Behavior Analyst should be a primary consideration for families in these situations.

Understanding ADHD and its Behavioral Loop

ADHD, or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, relates to a chemical imbalance affecting how individuals control impulses and focus their attention at a biological level. This imbalance significantly influences their behavior, leading to specific behavioral patterns in how someone with ADHD engages with their environment and crucially, how the environment reacts in response.

Every person, including children with ADHD, learns from the responses they receive from their surroundings. This constant feedback loop adds insights into which behaviors trigger specific environmental reactions. This learned response system stems from understanding when to avoid challenging tasks, how to garner desired reactions, and how to access preferred items or activities.

Everyone uses this information to guide their behavior decisions. However, for children with ADHD, this feedback loop can swiftly elevate maladaptive behaviors over functional ones. These disruptive behaviors, while easier to engage in and often producing immediate desired outcomes, contribute to a cycle. These learned behaviors, coupled with the responses of teachers and parents, create a substantial history of problematic behaviors, reinforcing and worsening the underlying chemical imbalance.

This is where behavioral therapy plays a pivotal role. It intervenes precisely when learned behaviors amplify the effects of the chemical imbalance based on how individuals interact within their environments. Addressing these learned behaviors through therapy becomes essential to redirect the feedback loop towards more adaptive and functional behaviors, countering the negative impact of the underlying imbalance.

In essence, the interaction between behaviors and environmental responses creates a feedback loop that significantly affects children with ADHD, emphasizing the critical role of behavioral therapy in reshaping these learned behaviors for a more positive outcome.

We know that medication can be hugely helpful for kids with ADHD symptoms—but we also know medication alone is seldom a silver bullet and non-pharmaceutical interventions can be powerful agents for change in the lives of children with attention deficit feedback loop histories.

Benefits of Behavioral Intervention for ADHD

Behavioral interventions serve as a meaningful option for parents who are hesitant about ADHD diagnoses or uncomfortable with medication. These interventions can profoundly impact a child’s well-being and serve as a stepping stone toward assessing the necessity for medication.

Such children might be identified by their teachers due to struggles with attention, consistency in routines, not actualizing their potential, or displaying their “best effort”. Teachers may not that these children become frustrated easily, express anxiety around time assignments, need frequent reminders to attend to tasks at hand, or are developing a reputation as a “bad kid”.

Well-designed behavioral interventions can be game-changing for the children described above. At this point, parents might be thinking “My kid isn’t badly behaved, so why should they need behavior therapy?” Effectively designed behavioral interventions not only reduce problematic behaviors but also enhance skills and adaptive behaviors crucial for success in school. They focus on decreasing undesirable behaviors while simultaneously fostering behaviors conducive to academic success.

For example- if a child is staring vacantly instead of attending to their teachers, a behaviorist might describe goals for them in two ways:

- Reduce the behavior of “spacing out”(staring at nothing, in particular, not visibly attending).

- Increase the behavior of being “on task” (looking at the teacher, taking notes, interacting by asking relevant questions, etc).

Implementing change through ABA

There are plenty of ways a BCBA might tackle this challenge. One of the most popular methods is called a Token Economy, often recognized as a “sticker chart.” This approach rewards desired behaviors, redirecting attention towards positive actions rather than disruptive behaviors. For instance, once a child has collected enough tokens/stickers, they can trade them in for a preferred prize. So, for our child who is “spacing out”, we may start by giving them a sticker for every minute they are displaying “on task” behavior. As they become successful, we would fade the frequency of sticker reward to every 3 minutes, every 5 minutes, every 10, etc., until they no longer need the reward.

Regardless of whether your child meets the criteria for a diagnosis, if spacing out is a consistent problem for them at school, a properly implemented Token Economy will meet them where they are and guide them to where they need to be by teaching and attending at the same time as they are learning whatever subject is being imparted.

It sounds simple, but the problem is, it’s pretty complicated. Plenty of well-meaning educators try to implement such procedures in their schools and classrooms, but without specific behavior training can design token economies in a way that will make things worse. This is in no way a dig at educators—their job is to teach a whole group of kids. One child who has different needs can’t always come before the rest of the class. Teachers might not have the time or resources to research individualized behavior strategies while tackling the many, many other tasks they have on their plates.

This is where a Board-Certified Behavior Analyst can play a pivotal role. They can develop tailored behavioral plans, assist teachers in implementing these strategies, and train parents to reinforce them effectively.

ABA stands as a powerful ally in addressing ADHD-related challenges. Whether used independently or in conjunction with medication, a Board-Certified Behavior Analyst can be a huge asset here. BCBAs can go into schools, observe, write individualized behavior plans (that a teacher can comfortably enforce in a classroom setting), and train parents and teachers to implement them as well. These systems, when written properly, are designed to be faded so children will not need them permanently. If a child can be successful without medication or needs support in addition to medication, a BCBA at Manhattan Psychology Group would be happy to help support your family.

Russia’s attack on Ukraine has been a top story in the media

Francyne Zeltser, PsyD, Child, Adolescent and Adult Psychologist and Clinical Director of Psychology at Manhattan Psychology Group, offers tips on how to discuss news like the Russia-Ukraine conflict with children:

1. Don’t drive the conversation; follow the child’s lead

Allow children to tell you what they know about a topic rather than sharing with them outright to understand the scope of information. “Instead of asking ‘Have you heard about the war in Ukraine?’ you can ask, ‘Have you heard anything in the news lately?’” suggests Dr. Zeltser.

2. Debunk any of the child’s misconceptions

It is important that the child does not have false information, which can lead to confusion or unrealistic expectations. Dr. Zeltser says, “Let the child tell you what they know, then share age appropriate facts with them and clarify inaccurate ones.

3. Break down complex concepts using child-friendly analogies

Talk about facts that are understandable for children. “You don’t have to explain something intricate like sanctions, for example, but find relatable parallels for children,” Dr. Zeltser explains. “You could say, ‘Every single country has someone in charge, like how your school has a principal. Let’s say each classroom is a country, each teacher is president of the country, and the principal is NATO. If the country isn’t doing the right thing, NATO can come in just like the principal can come into a classroom.”

4. Provide historical context for better perspective

“It will help reassure the child’s safety to understand that these frightening events have happened before, and we are here safely,” Dr. Zeltser states. You can reference wars that have occurred in the past, explain why they occurred, and tell how they ended in simple language. “If you provide children with education on war and what it means, they can have less fear of these unknown events.”

5. Use a map to assure children they are safe

If you place the war in Ukraine in a global context, your children will better understand that the violent events are not going to happen at home. “You can reassure children through a geography lesson,” Dr. Zeltser shares. “On a map, point and say ‘This is where we live. This is how close home is to school, and this is how close home is to where the war is right now. It is far away from us.”

6. Address children and families in a war crisis without instilling fear

The war is impacting children in Ukraine, and you can address it with children through a more supportive outlook. Dr. Zelster says, “You can tell children, ‘Right now, families in Ukraine are fighting to be together. Parents are doing everything they can to keep their children safe. Some family members there are involved in the war, and others are working together to support the children as best they can.’”

7. Suggest ideas for ways they can help people in Ukraine

Thinking of actions that children can take from afar to help families in Ukraine can instill a sense of involvement and change in them. “We can talk with children about how they can write letters, provide supplies, or donate money to offer shelter and safety,” Dr. Zeltser offers. “Even if kids just give five cents, they can feel like they’re making a difference.”

Over the past three years, external stressors surrounding the impact of COVID-19 left many people in the workforce feeling exhausted, unmotivated, and overwhelmed with keeping up with the daily flow of life. Adults with school-age children were put under increased stress maintaining occupational responsibilities while trying to navigate the educational transition to remote learning. Daily living was even further exacerbated for families with children in need of specialized services (Jimenez-Gomez, 2021).

Causes of High BCBA Burnout

Workers in social services and client care industries were pushed to their limits often putting the care of others before their own. In a sample size of over 800 ABA practitioners, including behavior technicians and Board Certified Behavior Analysts (BCBAs), 72% reported medium to high levels of burnout. (Slowiak, 2022). Exhaustion and disengagement can lead to absenteeism, turnover, and physical health deterioration (Plantiveau, 2018) which can have negative ripple effects on an already vulnerable population who receive behavioral services. Furthermore, burnout and high turnover rates are costly experiences for providers, organizations, and clients as the constant need for training can lead to resource depletion of time and energy, as well as disruptions in service delivery for all involved (Slowiak, 2022).

Burnout has been described as a work-related state of exhaustion, exemplified as extreme tiredness, emotional and cognitive impairment, and mental distancing (Otto, 2021). Burnout is a prevailing issue amongst ABA practitioners, with a number of factors contributing to the result. It is important to be aware of the environmental variables that could be acting on the practitioner when observing and assessing burnout, as well as early indicators to be conscientious of to mitigate symptoms.

Burnout is most often caused by prolonged exposure to work-related stresses. This can include an imbalance between demand and resources, as well as conflict in the workplace. Conflict in the workplace can include supervisors, coworkers, and clients. There can even be conflicts between demands for the role and personal preferences (Plantiveau, 2018). Furthermore, unrealistic expectations, challenging student behavior, and lack of training or administrative support can be contributing factors to job dissatisfaction and turnover, as well (Plantiveau, 2018).

The Buildup of Burnout

Burnout often takes place over a prolonged period of time, and it can often be difficult to notice when it is occurring. There tend to be a common set of symptoms associated with burnout that can act as early indicators to mitigate onset if identified early enough. If broken down into three general categories, burnout can present as emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and lack of personal accomplishment (Jimenez-Gomez, 2021). This can manifest in a deterioration of physical health, a lack of motivation to go to work, feeling ill-equipped to complete the work assigned, or feeling like you can no longer put the needs of the client before your own.

Ways to Reduce Burnout

Douvani et al. (2019), found that half of all BCBA professionals had only worked with one to two clients before certification. Furthermore, 50% of all certified behavior analysts were certified in the last 5 years (BACB, 2022). This strengthens the case for the repeated findings that high quality training and ongoing supervision are two of the biggest factors in mitigating burnout amongst employees (Douvani et al., 2019). While organizations can attempt to reduce burnout through fostering more positive work environments and high quality training, unfortunately, meta-analytical reviews have displayed that employer-initiated interventions have lasting, yet little effect on burnout prevention, leaving the burden of responsibility ultimately on the employee (Otto et al., 2021). Luckily, there has been an increase in research towards self-initiated preventative burnout interventions, and results show early signs of success (Otto et al., 2021).

One of the difficulties with addressing burnout is that by the time symptoms are identified, intervening with the behaviors needed to mitigate the symptoms can often be stressful just to think about. Thus, taking preventative measures prior to the onset is proven to be the most effective approach (Slowiak, 2022). Much of the research surrounding preventative measures when addressing burnout circles around the importance of self-care, mindfulness, and time management (Eberhart, 2019). This can take the form of engaging in activities that you care about or find enjoyable, setting limits with your clients and supervisors as to how much work you can manage, knowing your own triggers as it relates to burnout, and finding ways to contact reinforcement both inside and outside your work environment.

Rethinking Work-Life Balance to Mitigate Burnout

One common narrative as it relates to self-care is the notion of maintaining a work-life balance. Far too often this concept gets split into a dichotomy indicating that work and life should be two separate experiences with clear boundaries. However, work is inherently a part of life, and work can and should be fun. This takes place through finding meaningful work to engage in, so that feelings of satisfaction are experienced when time has been considered to be well spent. Slowiak (2022) rejects the word “work-life balance” and instead chooses to call it “work-life flow” as the two aspects of our life more often than not tend to blend together. She continues by outlining parameters of work self-care and personal self-care, and how they intertwine.

Personal and Professional Self-Care

Self-care can be described as a set of behaviors that an individual engages in on a daily or regular basis (Slowiak, 2022). The domains of self-care can be split into the following categories:

- Physical: Sleep habits, engaging in physical activity, or illness prevention

- Psychological/emotional: Practicing mindfulness, labeling triggers, or recognizing and using personal strengths

- Social: A support system through close relationships or community

- Leisure: Such as playing sports, knitting, spending time with a pet, or however an individual chooses to “recover”

- Spiritual: Finding purpose, reflection, spending time in nature, or religion

It is important to establish strong self-care routines first, as these act as a prerequisite to developing professional self-care behaviors.

Slowiak (2022) then went on to outline a number of different domains to encompass how professional self-care presents in the work environment:

- Professional support: Maintaining supportive relationships with our colleagues & avoiding isolation. It is important to create sustainable relationships over time, and this can be done through sharing both rewarding and stressful work experiences.

- Professional development: Finding continuing education opportunities that match your interests on a professional level and personal level. Additionally, picking channels of information dissemination that cater to your learning or finding it through the organization. This can be trying to find something at work that can tied to your personal values.

- Life balance: This is the dichotomy of work-life balance. The pandemic blended the two and, ultimately in our life, they are a part of one another. This could be reading emails on the treadmill or leaving all work at the office. This is based on personal preference.

- Cognitive awareness: This stresses the importance of psychological self care, andbeing able to tact our triggers and alter our responses. This is through self-monitoring and self-reflection, which tend to result in increased positive feelings and feelings of personal accomplishment

- Daily balance: This is the small scale, day-to-day, hour-to-hour, minute-to-minute awareness of self needs. It includes taking micro-breaks or practicing grounding techniques to break up the work day.

Defining Job Crafting and Its Success Against Burnout

Recent research has also indicated job crafting as a successful strategy to mitigate burnout. Job crafting is a job redesign strategy and a method of engaging in professional self-care. It involves initiation by the employee in making tweaks and changes to their professional life as a response to job demands (Slowiak, 2022). This can be through changing the quantity of work agreed upon, managing deadlines, setting meetings to occur at more preferred times of day, varying types of clients across cases, or reducing less preferred non-client related activities. Ultimately the goal is to increase the fulfilling and challenging aspects of the job while decreasing the hindering aspects of the job as they pertain to the individual’s personal preferences.

Addressing Burnout and Social Health

Burnout has nothing to do with yourself, it is merely an indication that there is something wrong with the current structure in your life. Given the nature of the field of behavior analysis and the client population that it serves, it is understandable why burnout would be so high. Luckily, there are a number of preventative strategies that can be taken to mitigate the onset of symptoms. Utilizing these strategies can help BCBAs maintain high levels of energy and effectiveness when providing services to their clients, and hopefully lead to a decreasing trend in turnover over time. Addressing the social health concerns surrounding burnout has been an ongoing issue for a number of years. With burnout affecting everybody from providers to parents to caregivers, (Shaikh, 2022) and even children on the spectrum (Mantzalas, 2022), it is of the utmost importance that the body of research on effective interventions continues to grow. Thankfully, it is reassuring to know the number of BCBAs continues to grow, and there is no better profession to assess the variables surrounding burnout and develop a path towards positive change than that of a behavior analyst.

Behavioral Parent Training Workshop for Parents of Kids Ages 0-6 & 7-12 presented by Dr. Joshua Rosenthal on the UWS on 9/25/16. There were nearly 75 parents in attendance learning new skills and practicing role plays!

Workshop Description:

When children don’t listen, how do you stay calm and not lose your temper? How do you know which strategies to use for each situation? Based on years of clinical experience and the latest research, Dr. Rosenthal teaches parents specific and concrete skills and scripts that really work. Parents will learn how to reduce conflict and prevent typical child behaviors from becoming bigger problems. Warning! This is not a boring, passive lecture. This workshop will be fun and engaging and may cause serious improvements in your parenting skills!

Videos of Dr. Rosenthal at the workshop:

https://youtu.be/D-9UhNalGgU

https://youtu.be/xGPRMSOY6mo

https://youtu.be/fjeY-hn-_VM

https://youtu.be/gAPJb7JZzjY

Testimonials from Parents Who Attended:

https://youtu.be/JLjt5RgkIrU

“After years of therapy, including parenting coaching, this session was the most informative, efficient use of time. The biggest challenge now will be putting it into practice.”

“I’ve read books, attended parenting seminars and worked with specialists before but this was simple, practical and easy to put into practice immediately.”

“I found the workshop very helpful. Dr. Josh was engaging and made it fun. I liked that he provided specific examples to understand the skills being taught and that he also gave some time to practice the skills. ”

“Dr. Josh has a lot of empathy for parents.”

“Dr. Josh offers great coping strategies to help impact our communication with our daughter. It has has helped her behave and respond more appropriately.”

“Excellent, practical approach to helping a family manage skills of a growing child.”

“Very helpful! Even for parents with a not especially troubled or difficult child. Tools that are helpful to all parents.”

“Dr. Josh gives concrete tools as to how we could parent better and empower us. Creating an environment where we all feel we have similar problems was very helpful. Highly recommend this workshop and looking forward to trying these tools.”

“Nice overview of using positive praise and picking your battles with your children. Dr. Rosenthal teaches methods of active ignoring to get your child to listen.”

“Came out feeling like I learned so much. Josh gave us the tools to handle multiple situations we face everyday.”

“A very informative workshop chock-full of practical advice that every parent can use. I would highly recommend this to anyone.”

“A straight forward, no-holds bar approach to parenting techniques. Simple steps any parent can implement right away to change the current environment for the better.”

Written by Sudha Ramaswamy, PhD, BCBA-D, LBA

Learning about early developmental milestones for babies and toddlers is one of the most important things that a parent or caregiver can do for their child. Signs of autism can appear as early as a few months and most often before a child’s second birthday. There are important social and language milestones to look for as your child grows. You can observe your child’s development by watching how he or she plays, learns, speaks and even non-verbally communicates. Read on to learn about milestones to watch for in your child and some activities that you can engage in with your child to facilitate their development and growth. Early developmental milestones for babies to toddlers nine months to two years old are outlined below. If your child is not meeting these milestones or if you have any other concerns, talk to your pediatrician.

9 months

By 9 months of age, babies should be making eye contact with you and smiling, often babbling while looking at you. They should copy your gestures and sounds. They will also demonstrate their needs by reaching for items that they want. Often by 9 months, babies start to play back-and forth games such as “peek a boo”, can transfer toys between her hands and look to where you point. You can encourage your baby’s development by playing games with “my turn, your turn.” Say what you think your baby is feeling. For example, say, “You are so sad, you fell down!”. You can describe what your baby is looking at; for example, “purple, bouncy ball”. Narrate what your baby wants when she or he points at something, for example, “yes, that’s a big truck!” Copy your baby’s sounds and words when they babble to teach them that their words pay off.

12 months

By 12 months, babies will play more social games and engage you with eye contact while playing. They will also use gestures like pointing to indicate their wants and needs. By 12 months, babies will begin to use consonant sounds and a few simple words, like “mama” or “baba”. At this age, children are very inquisitive about the world around them. Parents can make the most of this natural curiosity by engaging children in conversations about the objects or activities that have captured their attention. By tuning in and talking to children about whatever is holding their attention, adults have an opportunity to support children’s language development by responding to their interests. Parents can use these moments to support children’s language by initiating high-quality conversations that include rich vocabulary.

18 months

By 18 months, children will plays pretend with dolls or stuffed animals and can use at least 10 words. They will continue to imitate your words and actions while playing. Children will start to make many different consonant sounds and identify familiar people and body parts. Toys can also be helpful in providing children with opportunities to practice their communication skills. By choosing materials that can encourage children to talk or listen to an adult or a peer, teachers can supply children with “props” to help support children’s language development. These props are objects that may stimulate conversations and include dolls, old phones, puppets,books, pictures, play dough, and legos. When using a prop, adults can ask children open-ended questions like “What…?”,“Why…?” and “How…?” Then, pause for a response. Parents can also label props and provide explanations about their function or purpose.

Reading books to children is one of the most effective ways to provide children with opportunities to develop their social and language skills. Parents and caregivers can use books to start discussions with children about the stories and pictures presented and connect the stories and pictures to children’s lives. The opportunities for helping children build their language skills with books are greatest when adults help children to become engaged by: 1) encouraging children’s participation in the story, 2) expanding on children’s responses, and 3) giving feedback. By interacting with children in these ways, parents and caregivers give children a chance to practice listening and speaking skills that foster language development.

24 months

By 24 months, children show a definite interest in playing with other children, but they still spend more time in parallel play (next to other children), rather than interactive (with other children). They can put many actions together during play, like stirring, pouring, or giving a doll a bottle. Children’s vocabulary has rapidly expanded to at least 50 words and they can identify objects when named. By two years old, children can make simple sentences like “Daddy, go outside” and “What’s that, mommy?”. Encourage your child to help with simple chores at home, like sweeping and making dinner and encourage conversation during these chores to practice using new vocabulary. Praise your child for being a good helper and following simple directions. At this age, children still play next to each other and don’t share too well. For play dates, provide children toys and activities to play with together. Observe the children closely and step in with models for appropriate language during play, for example, “Can I play with that please?” You can review rules for positive peer interactions ahead of the playdate to reiterate expectations for appropriate behavior. For example, “use your words”, “take turns” and reinforce all opportunities when your child is using this language appropriately. If problem behaviors arise during play (e.g. crying, grabbing etc), model correct language for your child.

Early intervention makes a critical difference

If you notice that your child is not meeting milestones, reach out to your pediatrician who can provide support for obtaining early intervention evaluations and services. Oftentimes, even though parents have certain concerns, they may put off seeking help from a professional. Parents may be waiting to see if their child grows out of certain behaviors or may be unsure if what their child is showing is a real concern. Research shows that early intervention is crucial to improving outcomes for kids with autism and related developmental disabilities. The early time in a child’s social and language development is critical. Remember, it is never too early or too late to provide support for your child.