There are approaches to communication and signals to pay attention to regarding your child’s mental health that can help them thrive as they return to school.

1. Talk it out together to ease anxiety

Discuss classes and pieces of school or extra-curriculars outside of the classroom to balance talking about things your child might feel nervous or excited about.

2. Frame your questions thoughtfully

Ask questions about what’s going well, but also about what’s not going well to get the full picture. Ask “What’s challenging?” instead of “Why is it challenging?” to remove any signal of accusation and help your child open up more, because they are less likely to feel defensive.

3. Look for changes in your child’s behavior

Make note of increased irritability, changes in appetite or sleep habits, or a loss of interest in their activities. These could be signs that you’re child is struggling with depression, anxiety, or another mental health challenge.

While temporary behavioral changes can be considered a normal part of adjustment to the back to school routine, if they continue beyond the back to school period or create disruptions in your child’s day to day life, we recommend you seek professional help.

4. Listen and offer support so they know you’re there for them

Communicate clearly that you are available if your child wants to talk, and seek additional resources – from books to journals to a licensed therapist – if you think they need additional help.

Mental healthcare is healthcare. From parents to professionals, additional support for students can make a meaningful difference.

For more information on our Special Group Programs or treatment options for children and teens, contact us.

How is ACT different than CBT?

ACT differs importantly from other talk therapies such as CBT because rather than focusing on changing maladaptive thoughts, ACT emphasizes acceptance of all psychological events, and therapists concentrate their attention on how a person’s behavioral responses to these events work for them in terms of their self-identified values or goals. The focus on increasing acceptance within ACT has been shown to increase self-esteem and resilience (Black, ACT for Treating Children, New Harbinger Publications, 2022).

How is ACT modified for children?

When treating a client with ACT, practitioners use something called the ACT Hexaflex, which was developed for adults. The ACT Kidflex has been adapted for younger clients and encompasses the same six core ACT processes, which include: acceptance, defusion, values, committed action, contact with the present moment and self-as-context. When working with children, practitioners might borrow the modified Kidflex language from Dr. Tamar Black and teach them: Notice yourself, let it go, let it be, stay here, choose what matters, and do what matters. Together the goal of these processes is to increase psychological flexibility. Hayes et al (2006) defines psychological flexibility as “the ability to contact the present moment more fully as a conscious human being, and to change or persist in behavior when doing so serves valued ends (Black, ACT for Treating Children, New Harbinger Publications, 2022).” In other words—be mindful and present and adjust your behaviors as necessary.

The Core ACT Processes when working with children

Let It Be

“Let it be” refers to letting undesirable private experiences exist, without trying to change, modify or eliminate them. Behaviorally speaking, a private experience is something that an individual experiences that are not visual to an outside observer. Thoughts, emotions, memories, and physical urgers are private experiences. You might be thinking that there are plenty of times when mitigating an unpleasant experience is preferable and adaptive, and you’d be right. Letting my two-year-old watch a five-minute YouTube video on my phone while she got her hair cut for the first time reduced her anxiety and made it less likely that she injure herself flailing in a panic around scissors. After getting her hair cut once and realizing she liked the outcome, she wasn’t afraid anymore and no longer requires a video to stay calm. For a short, discrete event, these distractions can be adaptive. When a long-term stressor exists, this strategy stops being adaptive. For example, if my child wasn’t very good at soccer and felt self-conscious about it, they might stop going to soccer practice. Having social time with their friends on the soccer team might be important to them, and the outcome of missing soccer practice would lead to less social opportunities which then leads to stress. As a result, the long-term strategy of avoiding their thoughts and feelings about not being very good at soccer is not serving them well. An ACT therapist would counsel this child to observe their feelings of discomfort with their soccer skill level, without trying to change them, and then gently bring their attention to what their goal is, whether that is socializing or practicing a soccer skill so practice can feel less uncomfortable.

Let it Go

“Let it go” means putting some distance between our thoughts and ourselves so we are not stuck or attached to them. Thoughts do not need to be eliminated or replaced. Let it go involves teaching children to see thoughts for what they are without letting them have power over us. My soccer-anxious child might say to herself “I am having the thought that I am bad at this and everyone knows it.” This response encourages the child to see their feelings and thoughts as just feelings and thoughts, not facts or laws. This makes it easier to give that thought or feeling less power and do what matters even when the thought or feeling is present.

Choose What Matters

“Choose what matters” refers to a client’s values. What that person cares about and is willing to work on. Values differ from goals in important ways. Goals can be temporary events with a final outcome. The goal for my soccer player may be for her team to win a game, but the value (for her) is her connection to her team.

Do What Matters

“Do what matters” are the behaviors that tie into the values identified in “choose what matters”. In this respect ACT can look a lot like a more traditional behavior therapy. ABA strategies like shaping, exposures and skill acquisition can all be utilized when helping clients learn to “do what matters”. For our example of the soccer player, do what matters would mean go to practice and connect with your team.

Stay Here

“Stay here” endeavors to help individuals remain present with uncomfortable thoughts or feelings without trying to minimize or dismiss them to be present and functional. When trying to encourage my child to “stay here” during soccer practice, I may encourage her to notice how the ball feels against her toes, the smell of the grass, or the sound of her foot against the ball when she kicks.

Notice Yourself

“Notice yourself” aims to teach clients to see what they are doing and what the impacts of their behaviors are. Clinicians might tell a child to imagine they are a ghost, watching themselves, and ask what do they notice? A child might notice “When I come home from school and feel cranky or tired, I go to my room and play video games until I start to feel differently. But wow, after floating around observing myself, I’m realizing that I spend a lot of time playing video games while my family is together. I’m missing out on time to be with them.” As a result of this exercise, a child may start noticing at home when they are missing out on other opportunities and change their behaviors, even though the emotions that led to those behaviors haven’t necessarily changed.

In concert, the goal of all these core processes is to help kids become flexible. Some kids already have mastery over one or more of the core processes, and might only need to address one or two. Others may need coaching on all six. Your child’s ACT clinician will help make those assessments.

Manhattan Psychology Group’s evidence-based focus team of therapists are especially qualified to provide this behaviorally rooted therapy. If you think ACT could be a good fit for your child, please reach out to us!

Depending on your family’s circumstances in dealing with Coronavirus, some of you might have already been self-quarantined in your home before this week. Many more of you who might have children in the New York City public schools could be planning to transition to working from home, due to the recent shutdown. If so, there are bound to be some new challenges as a family, regarding childcare, education, finances, health/safety, personal and marital issues, and access to resources. Many families are not used to spending so much “quality time” together while NOT on vacation.

Depending on your family’s circumstances in dealing with Coronavirus, some of you might have already been self-quarantined in your home before this week. Many more of you who might have children in the New York City public schools could be planning to transition to working from home, due to the recent shutdown. If so, there are bound to be some new challenges as a family, regarding childcare, education, finances, health/safety, personal and marital issues, and access to resources. Many families are not used to spending so much “quality time” together while NOT on vacation.

My recommendation is to lean into it. Take this opportunity to reconnect (emotionally and virtually) with loved ones and grow as a person, parent, partner, and professional. As with any adjustment or transition period, there will be stress. What’s important is how you cope with that stress.

Here are some tips to reduce stress and better cope:

1. As a person – Being at home for long stretches of time will not be easy for most adults. Choose healthy ways to cope with stress, such as exercise, talking, therapy, reading, making art, cooking, cleaning, organizing, and learning. Try to avoid too much screen time, emotional eating, substance use and other activities that disconnect you from the moment and loved ones. As the adult, those around you will turn to you to set the tone, so your behavior will become a model, whether you intend to or not. For example, it’s perfectly reasonable to tell your child or partner, “I’m feeling very stressed right now, so I’m going to go read by myself for 10 minutes and then I will come back when I’m calmer.” Stretch yourself by doing activities and engaging with your family in new ways. This virus could impact society for months to come so plan for long-term change.

2. As a parent – This means many things. First, keep yourself and your family safe by following the CDC precautions. Second, try to stay calm. Children will respond to your affect and behaviors. If you seem stressed and agitated, it will dysregulate your children. This can present in many different ways depending on the child, such as increased tantrums, loss of appetite, increased negative attention seeking and sleep refusal. It’s ok to share with kids that you are nervous or stressed – this explains your behavior and normalizes the situation. Just make sure not to overshare and keep it developmentally appropriate. Third, children at home will need a regular routine and the day to be broken into chunks, just like school or daycare. So will the adults. This should start with a regular wake up and bedtime, which will make keeping a routine throughout the rest of the day easier. During the day, try to create a mix of “work/academic” and fun/play activities, both inside and outside. The more you break things up, the faster the time will go. Screen time should still be limited and used as a reward or for work only. Finally, explain to your children what’s going on in developmentally appropriate ways, especially if you are self-quarantining in your home, someone is already sick and/or one parent is now working from home full-time.

3. As a partner – If you live with a partner, my recommendation is to increase communication, not pretend like everything is the same. During stressful times, you want to try to communicate more, not less. This means telling your partner what you need from them and what they should expect from you. No one can read your mind, no matter how upset you are or how obvious you think the issues are. Such close physical proximity will be stressful for some couples who are not used to being home together all day while working and caring for the children. Try to set up clear boundaries and time limits around working, spending time apart, and spending time together as a family. Try to have empathy for your partner as they are probably under a tremendous amount of stress and may have uncontrollable worries about the future.

4. As a professional – Flexibility is key here. As the boss or owner, your staff will be looking to you for guidance. Stay in regular contact with your staff so that they know that you care about them, especially if you are no longer in the office and/or have staff that work remotely. Stay calm. Don’t make any drastic changes. Your staff will feel unsafe if you act impulsively or make changes that negatively affect their current work load or pay. Give as much notice as possible before making any changes and explain why. Your staff will understand if you come across balanced and thoughtful. If you are an employee or independent contractor, stay focused on the tasks before you. Continue to do great work and showcase yourself as a reliable and professional team player. When the dust settles, your boss will recognize which staff stepped up and which staff were more of a burden to the company.

Regardless of your living or work situation, COVID-19 will impact everyone. Interpersonally, the question is – how will you cope with it? Will going through this difficult time strengthen your relationships or damage them? In my opinion, nothing strengthens a relationship more than making it through a stressful time together!

What is Ableism?

“Ableism is the discrimination of and social prejudice against people with disabilities based on the belief that typical abilities are superior. At its heart, ableism is rooted in the assumption that disabled people require ‘fixing’ and defines people by their disability. Like racism and sexism, ableism classifies entire groups of people as ‘less than,’ and includes harmful stereotypes, misconceptions, and generalizations of people with disabilities.” (Eisenmenger, 2019).

How does Anti-Ableism Impact ABA Therapy?

Ableism is a form of social prejudice that affects people across all different kinds of physical disabilities such as blindness or paraplegia (wheelchair users). In addition, ableism also affects people who have developmental disabilities such as individuals with Down’s Syndrome or autism spectrum disorders (ASD). As behavior analysts (BCBA), we are specialized in modifying behaviors. According to a survey from the Behavior Analyst Certification Board in 2021, over 70% of BCBAs service individuals with ASD (BACB, 2021). Developing and writing up ABA goals is one of the most important responsibilities of a BCBA. They help set the foundation and framework for the goals and skill building. When working on these goals, it is especially important to consider how the behavior analyst can develop a goal that is ethical and evidence based. But it is also crucial that the behavior analyst thinks with an anti-ableist mindset during this process.

The following includes some recommendations and considerations (in regards to thinking anti-ableist) when beginning the process of goal writing:

1. Don’t “teach to stop” repetitive behaviors

A common question that parents have asked me is, “how can I get him to stop stimming?” A common symptom of ASD is the presentation of repetitive (aka “stimming”) behaviors. Some common examples include: clapping hands repeatedly, echolalia (repeating sounds or words without any social context), and rocking back and forth. Repetitive behaviors such as these are not often dangerous to the self or others, and are often thought of as “self-regulatory” or “self-soothing” behaviors (Kapp, 2009). Because these behaviors tend to be thought of as “disruptive” or “bothersome” by others, it is important to consider this from an anti-ableist perspective.

My view on repetitive behaviors fully takes into consideration anti-ableism. I feel that regardless if a person has autism or not, we all have our own different versions of “self-soothing” behaviors. For me, when I am nervous I like to squeeze my hands together as hard as I can. I find that it helps me to soothe myself in moments of this kind of distress. On some days when I’m feeling really happy, I like to jump up and down and give hugs to all my loved ones. Think of it in this way when it comes to our kids with ASD! They have their own version of behaviors that calm them as well.

Instead of objectifying these kinds of repetitive behaviors to be subject to being treated through behavior modification, consider creating a behavior plan that educates yourself and the client’s family on why their child is exhibiting these behaviors. The behavior plan should never seek to eliminate these behaviors if these behaviors are indeed just for sensory processing reasons. At the very least, we can develop a behavior plan that can help teach the client how to control these impulses and behaviors depending on the time and place. For example, you can use stimulus discrimination teaching procedures to teach the client that they can jump and down and scream inside their bedroom with the door closed, but not in the living room.

2. Don’t ever underestimate the child’s abilities!

“I don’t think he can do that… He doesn’t even know how to read!” This was a comment from a parent that I worked with a long time ago. This was a case with a 7 year old boy who had non-verbal autism. We were discussing the idea of teaching him how to use a PECS on the iPad. At only 7 years old, this boy had a great set of skills: how to open up the browser and YouTube on the iPad, receptively identify things in videos, and even type on the keyboard for what he wants to watch!

A lot of times, parents will focus a lot on the negative things about their child when they have a disability. To consider this from an anti-ableist perspective, I always keep in mind that every child with a disability is capable of learning anything compared to a child without a disability. There will be without a doubt where you will hear discouraging comments as such, but just remember that the process of learning just might take some more time and a lot of patience. The right behavior analyst will keep this in consideration and never assume that their client is incapable of anything without even trying first!

3. Never force someone to change!

I strongly disagree with those who believe that, “ABA is coercive” or that we use ABA to “fix” or “change” their behavior or even “who they are.” It really pains me that there are some people who would agree with these beliefs! My job may be a BCBA most of the week, but my full-time job as a human being will always consider how others feel before myself. I do not think that any person with autism needs “fixing” or “changing.” Ultimately, human beings are subject to their own free will and decisions. This applies to our children that we work with as well. Before I decide to implement a goal, I always discuss it with the child first and then talk with the parents afterwards. By not doing this, it can seem coercive or that the child may feel like we are “changing” them. I want to make sure that they are aware and comfortable if the child wishes to work on the behavior in mind.

I bring the example of my friend’s 13 year old with ASD – “I want him to be outgoing. He is so antisocial! He needs to make more friends” she told me one day. The key words here are “want” and “needs”. It is the use of this kind of language that comes off as coercive or that her son needs “fixing.” Because one of the main features of ASD is an impairment in social-communication, my friend often assumes that the “anti-socialness” in her son is due to his ASD. However, I feel that this is not a problem that needs any fixing. Similar to my previous point, every human being is unique in their own special way. Some people are outgoing, and some are not.

I was able to quickly resonate with my friend how he feels because I am very similar to him in that regard. My ideal Friday night is spent at home with a scented candle lit, curled up with my partner and our pets, watching dumb sitcoms! Imagine how I would feel if someone told me that I needed to “change” that? Ultimately, our differences as human beings are not because we have something “wrong with us” like a disability!

4. Watch your language!

An article titled Avoiding Ableist Language: Suggestions for Autism Researcher recommends various considerations in an effort to reduce the use of ableist language. In their article, they describe language as a powerful means for shaping how people view autism. If researchers take steps to avoid ableist language, researchers, service providers, and society at large may become more accepting and accommodating of people with autism (Bottema-Beutel, 2021). The first section of their article shows a table of potentially ableist terms/discourse, and suggested alternative terms that are less ableist.

For example, words such as “challenging behavior” or “problem behavior” can potentially come across as ableist as it can seem like masking the child’s behavior. It is recommended that these terms be avoided all together and just simply describe what the behavior is and what it looks like. There are many more of these recommendations included in this article that are especially relevant to all ABA practitioners.

References

https://www.accessliving.org/newsroom/blog/ableism-101/

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/aut.2020.0014

Kristen Bottema-Beutel, Steven K. Kapp, Jessica Nina Lester, Noah J. Sasson, and Brittany N. Hand.Avoiding Ableist Language: Suggestions for Autism Researchers.Autism in Adulthood.Mar 2021.18-29.http://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0014

Most parents think of giving any type of praise as an instant motivation boost. But that’s not always the case when it comes to children.

In fact, several studies have found that when teachers give feedback to students, they convey messages that affect the students’ opinions of themselves and how capable — or incapable — they are of academic achievement.

And as a child psychologist, I’ve found that certain types of praise can do more harm than good to a child’s independence, learning drive, self-confidence and resilience.

How praise impacts your child’s mindset

Carol Dweck, a psychologist and professor at Stanford University, has been studying the impact of praise on children for decades.

In her research, she identified two core mindsets — or beliefs — about one’s own traits. These mindsets shape how people approach challenges:

- Fixed mindset: The belief that one’s abilities are carved in stone and predetermined at birth.

- Growth mindset: The belief that one’s skills and qualities can be cultivated through effort and perseverance.

People with a fixed mindset, she found, tend to ignore feedback, give up easily and measure success by comparing themselves to others. In contrast, those with a growth mindset are more likely to embrace challenges and make self-to-self comparisons.

Focus more on praising the process, not the outcome

By praising the process (“I love how you were very thoughtful about the colors you chose!”), and not the outcome (“The colors in your drawing are beautiful! You’ve got a good eye.”), is what helps children develop a growth mindset, according to Dweck.

When parents praise the outcome, it holds kids back from developing resilience, confidence and a desire to learn new things.

Imagine two kids on a track team. The first kid is a passionate runner, while the second is less athletic. The kid who loves running exerts minimal effort at practice and still wins first place in almost every track meet. The second kid pushes himself, but is discouraged by the fact that he hasn’t had a win.

To praise the process, the parent of the natural runner should acknowledge her skill without providing excessive celebration or praise. This will help her feel supported without suggesting that her innate ability is the primary factor in determining her success.

The parents of the less athletic child should praise him for his hard work and perseverance. This helps him maintain his self-esteem and stay motivated to succeed.

Teach that failure creates opportunity

To further support your child’s development of a growth mindset, move your sole focus away from their accomplishments and steer the same level of attention towards their imperfections.

Encourage them to recognize, accept and overcome their “weaknesses.” Remind them that they have the tools and support to grow in the ways that they want to.

Let’s say your child failed his math test twice in a row. Instead of responding with “well, this is disappointing” or “you’re not studying hard enough,” react to his failure as though it’s something that can enhance his learning.

Talk through questions like: “What is this teaching us?” “What should we do next?” “Maybe we can talk to your teacher about how you can learn this better?” This way, your child can come to understand that abilities and skills are not limited; They can be cultivated, and doing so can be a fruitful and wonderful experience.

Children who value learning and effort know how to make and sustain a commitment to their goals. They are not afraid to work hard, and they know that meaningful tasks involve setbacks. These are the lessons that will serve them well in life.

Francyne Zeltser is a child psychologist, adjunct professor and mother of two. She promotes a supportive, problem-solving approach where her patients learn adaptive strategies to manage challenges and work toward achieving both short-term and long-term goals. Her work has been featured in NY Metro Parents and Parents.com.

Don’t miss:

- A psychotherapist says the most mentally strong kids always do these 7 things—and how parents can teach them

- Psychotherapist: Parents of mentally strong kids always do these 3 things when giving praise

- Why psychologists say ‘positive parenting’ is one of the best styles for raising strong, confident kids

Can you believe that we will all say goodbye to 2022 in less than 30 days? This year has certainly flown past us in a blink of an eye. Before every year ends, I like to meet with parents to review and reflect on how ABA therapy has helped their child since starting services. This also sets up the stage for what we can plan to work on for next year.

This year, I have had the pleasure of working with families that are relatively new to ABA. I interviewed four different families who are new to ABA therapy. The purpose of this interview was to: (1) lend continued support for ABA therapy as an evidence based practice for helping families and children with ASD, and (2) lend continued support for parent counseling and training (PCAT) as an essential component of ABA therapy.

Q1: Has your perspective of ABA therapy changed at all since you first learned about it? How?

Parent 1:

“Definitely has changed. Good change for the better. When I first learned about ABA, my first experience was hearing it from other people and parents who probably had a really bad prior experience with it. “ABA will make your child like a robot,” was one of the most shocking comments that I first heard about it. I disagree with those kinds of comments completely.

I feel that since my son has started receiving ABA therapy, it has been the most beneficial service out of everything else. Working with an experienced BCBA has helped me understand how basic behavior science can be applied to help me understand why my son is behaving or acting out a certain way. These experiences have also helped me become a better parent that now only wants to learn more.”

Q2: What do you hope to achieve with ABA therapy?

Parent 2:

“I hope that ABA therapy can help my son become more independent and make his own decisions in life. Even though my son cannot talk with his own voice due to his disability, I hope that one day that ABA can help him communicate not just his needs and wants, but maybe one day his thoughts and feelings. As his mother, you can’t help but wonder, “What is my son thinking?” or “How is my son really feeling?” I am his one and only voice at the moment, and I hope that ABA can help him give him more of that ability to be autonomous.”

Q3: What kind of traits do you think make up a good ABA therapist?

Parent 3:

“I think the traits that make up a good therapist are traits that my child and the therapist have in common. It is just basic human nature to be able to connect more with other people who you share common interests with. For example, my son loves video games, Pokemon, and Anime, which are all things that I have tried getting into, but I just do not know as much as his therapist does. Children love when adults like the same things that they do.

My son’s therapist acts almost like a “big brother” role model to him in this way. He is able to incorporate learning opportunities that occur naturally which is incredibly brilliant and a refreshing way to teach these important life skills to my son. For example, one day his therapist was able to teach my son an important lesson on self-regulation skills during a really big tantrum he was having. Within minutes, his therapist was able to help him self-regulate and take perspective of the situation by using a technique called Behavior Skills Training.

It really helps when the therapist is both experienced in working with children who are a lot like my son, and also just extremely patient, communicative, and friendly. There is a warm and comfortable feeling that develops over time, once you begin to realize how lucky you are to find a therapist that truly cares and understands him.”

Q4: How do you feel supported in therapy and any recommendations in ways that we can support better?

Parent 4:

“I feel very supported in my son’s ABA therapy. I really like how his therapist always takes the time to speak with me to tell me what goals he is working on with him, what things he is doing well with, and what things he is having a hard time with. Communication is such an important thing here, especially when I can’t exactly sit down with my 8 year old with limited language skills and ask him, “So what did you learn today with your teacher (Andrew)?” It means a lot when they (the therapists) arrange the time to come visit our family at home.

Lately, there have been some moments when I do not know what is the right thing to do when my son is having a meltdown. It has been such a blessing to have a BCBA who can see his behaviors happen with his own eyes and immediately be there to provide feedback, recommendations, and support so that I can learn how to handle it on my own next time. I think that other BCBAs should do the same in which that they just spend a good amount of time seeing how the child’s family operates outside of the normal session hours to see if there can be any other behavior supports that can help not only me and my child, but provide support to my family members that share the same home and also take care of my son.”

Final reflections

We’re continuing to try to listen to the autistic community and their families, to ensure that we’re providing services that are leaving a positive impact. We encourage other BCBAs to take a moment to talk to their families at the year’s end on their thoughts, as well?

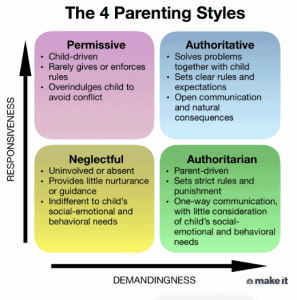

We all want to raise intelligent, confident and successful kids. But where to begin? And what’s the best parenting style to go with?

Parenting styles fall under four main categories. It might be that you use one or more of these different styles at different times, depending on the situation and context.

Research tells us that authoritative parenting is ranked highly in a number of ways: Academic, social-emotional and behavioral. Similar to authoritarian parents, authoritative parents expect a lot from their children — but they expect even more from their own behavior.

What is authoritative parenting?

Authoritative parents are supportive and often in tune with their children’s needs. They guide their kids through open and honest discussions to teach values and reasoning.

Like authoritarian parents, they set limits and enforce standards. But unlike authoritarian parents, they’re much more nurturing.

Some common traits of authoritative parents:

- Responsive to their child’s emotional needs, while having high standards

- Communicate frequently and take into consideration their child’s thoughts, feelings and opinions

- Allow natural consequences to occur, but use those opportunities to help their child reflect and learn

- Foster independence and reasoning

- Highly involved in their child’s progress and growth

Why experts agree authoritative parenting is the most effective style

Studies have found that authoritative parents are more likely to raise confident kids who achieve academic success, have better social skills and are more capable at problem-solving.

Instead of always coming to their kid’s rescue, which is more typical among permissive parents, authoritative parents allow their kids to make mistakes. This offers kids the opportunity to learn while also letting them know that their parents will be there to support them.

Authoritative parenting is especially helpful when dealing with conflict, because the way we learn to deal with conflict at a young age plays a big role in how we handle our losses or how resilient we are in our adult lives.

With permissive parents, solutions to conflicts are generally up to the child. The child “wins” and the parent “loses.” I’ve seen this approach lead to kids becoming more self-centered and less able to self-regulate.

Of course, there are times when a punishment, like taking a time out, is necessary. But the problem with constant punishment is that it doesn’t actually teach your kid anything helpful. In most cases, it teaches them that the person with the most power wins, fair or not.

Let’s say your 10-year-old son begs not to go to soccer practice: “I don’t want to because I don’t think I’m good at it.”

In response,

- A permissive parent might say, “It’s up to you.”

- A neglectful parent might say, “Whatever you want … it’s your life.”

- An authoritarian parent might say, “You have to. I don’t want to hear another word from you.”

- An authoritative parent might say, “I understand that you don’t want to go. But sometimes, fighting the urge to avoid doing something hard is how you get better!”

While authoritative parents do set limits and expect their kids to behave responsibly, they don’t just demand blind obedience. They communicate and reason with the child, which can help inspire cooperation and teach kids the reason behind the rules.

Authoritative parenting doesn’t guarantee success

While experts give authoritative parenting the most praise, it’s important to note that using just one method does not always guarantee positive outcomes.

Parenting isn’t an exact science. In many ways, it’s more like an art. As a child psychologist and mother, my advice is to be loving and understanding — but to also create structure and boundaries.

Don’t simply focus on punishment. Be supportive and really listen to your child. Ask them questions and try to understand things from their point of view. Allow them into the decision-making process so that they can grow and learn things on their own.

There’s a difference between parenting styles and parenting practices. A parenting style is the emotional climate in which you raise your child, and a parenting practice is a specific action that parents employ in their parenting.

In short, behave as the good human you want them to be.

Francyne Zeltser is a child psychologist, adjunct professor and mother of two. She promotes a supportive, problem-solving approach where her patients learn adaptive strategies to manage challenges and work toward achieving both short-term and long-term goals. Her work has been featured in NYMetroParents.com and Parents.com.

Don’t miss:

The research and methodologies of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) have progressed and modernized drastically since its debut in the late 1960s. ABA is a scientific philosophy, and it is a way of understanding human behavior to be used to its advantage serving as an evidence based practice. Brilliant behavioral psychologists during these past few decades have been able to come together and develop revolutionary ways of teaching new skills and modifying behaviors.

What is DTT?

Discrete Trial Teaching (DTT) is a well-known ABA teaching procedure developed by Dr. Ivar Lovaas in the 1970s. DTT is a one-to-one instructional approach used to teach skills in a planned, controlled, and systematic manner in which the learner is taught a skill separated into small repeated steps (Bogin, 2008). For example, if you were teaching a child how to read sight words, you would teach the same set of five sight words over and over until essentially “perfection” and no errors are made after a specified amount of consecutive sessions. To some practitioners, DTT may be perceived as “rote” or “highly repetitive” because DTT is sometimes characterized as “intense” and “repetitive” in its methodology. The amassed practice and repetition of learning trials can be beneficial for younger children (typically between the ages of 2 and 9) for teaching simple receptive skills such as tacting (labeling) objects, identifying colors, or following one-step directions.

DTT Challenges

However, using DTT can be challenging for teaching more advanced older learners more complicated or skills that require many steps such as: vocational skills, conversational skills, self-care skills, and many more. Most developmental disabilities such as autism are considered a lifelong disability. Therefore, DTT may not be the most appropriate teaching strategy for older children, teens, adults, and beyond. Luckily, there are many other options to choose from.

NET: An Alternative to DTT

Well-trained and experienced behavior analysts are aware of the many other teaching alternatives to choose from other than DTT. When I am providing direct ABA services, I prefer to follow a much more natural and relaxed teaching style. Natural Environment Teaching (NET) is also an evidenced based practice in which ABA practitioners incorporate the learner’s natural environment into the teaching, development, and generalization of skills. These learning experiences are incorporated into play activities using familiar toys, games, and materials to maximize the learner’s motivation to continue the activity. With NET, the learner is essentially in control of their environment and they have full autonomy on which activities they choose to do.

NET In Everyday ABA Practice

To best describe how and why I prefer to use NET in my everyday practice, I will explain the case of one of my 10 year old clients. Today, he returned back home after a long day at school (also a very long bus ride home!) and was very tired and he wanted to watch some of his favorite YouTube videos together on his favorite spot on the living room couch. This is very understandable, as I also like to do the same thing after being trapped in NYC traffic during the home rush hour almost every night!

I am thankful that I have such a wonderful and close rapport with him as his therapist. It is my presence and involvement in watching the videos together that has been the ultimate reinforcer for him since we have met. This gives me a teaching advantage during these situations in which I am able to provide natural teaching opportunities based on whatever he is choosing to watch. For example, today I was able to practice his expressive communication skills with learning to say, “again please” (for when he wants to hear the song again), “stop please” (for when he wants the video stopped), and “help me” (for whenever he would come across a technical issue with the computer). Because all of these situations were not contrived and occurred naturally, the learning experience becomes even more rewarding and meaningful. This also makes these target behaviors more likely to occur again.

Benefits of NET over DTT

Children are more likely to experience natural reinforcement outside of their therapy sessions when learning opportunities are incorporated into environments that are familiar to them. It is not worthwhile for them to learn how to memorize answers or responses through rote methods like DTT which are monotonous and not fun for the child. This is especially true if the learning experiences they acquire are not socially significant and do not functionally apply to their everyday environment. NET as an ideal teaching strategy is one of the many other ways that it can prevail over DTT.

For more information about the comparison between DTT and NET, please refer to the following article: https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2014-44014-007.html

References:

Bogin, J. (2008). Overview of discrete trial training. Sacramento, CA: National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders, M.I.N.D. Institute, The University of California at Davis Medical School.

It’s OK to feel sad it’s almost time for your kids to return to school, and/or relieved it’s almost time for your kids to return to school.

As families prepare to return to school in the coming weeks, here are some tips for success for a smooth transition from summer break:

1. Ease anxiety through familiarity: Tour the school or meet the teacher, and schedule a play date with a classmate or plan a carpool in advance. Preparing your child for a new school, classroom, and friendships and calm their concerns.

2. Don’t force your child to cram for class! Last minute academic prep can make a child feel like they did not prepare enough for school over the summer, and can heighten their feelings of anxiety. To get back into the swing of learning, try educational opportunities they enjoy, like reading, playing a board game, or working on a puzzle together.

3. Reset for your school routine: Ease back into your child’s morning wakeups and evening bedtime routine during the week before the first day of school. This will make the process a smoother transition for your child when school starts, and ensure they are well rested for it.

4. Talk through expectations: Discuss classes or extra-curricular activities your child will look forward to with them, in order to generate excitement over the return to school. But talk with them about classes or experiences they may not enjoy, as well, like a challenging subject or riding the bus. Talking through difficult emotions together can help them prepare for the more difficult events, and practice expressing their feelings for open communication with you through the school year.

It is natural for a child to begin a new school year with increased anxiety or changes in appetite, sleep habits, irritability, or other behaviors. If you do not notice them return to their “normal” selves after they have adjusted to their new school routine, however, or their anxiety, sadness, or emotions are disrupting their day-to-day life, we recommend you seek additional support from a professional.

For more information on our Special Group Programs or individual treatment options for children and teens, contact us.

ABA stands for Applied Behavioral Analysis. It refers to using scientific behavioral principles to manipulate a learner’s environment to help them gain skills quickly and effectively. ABA therapy, when done well, takes a unique approach to meet every learner’s specific needs, prioritizes caregivers’ goals and concerns, and flexes based on a family’s ability and/or willingness to implement treatment.

Punishment, as defined in the field of ABA, is simply something that happens after a behavior that reduces the likelihood of that behavior happening again. Punishment in these terms happens constantly in all our daily lives. For example, a few months ago I made my daughter slow roasted salmon over a citrus salad, and she told me it was “ahsgusting”. She effectively punished my behavior—I have not again made this meal for her dinner. In a therapeutic setting, it could mean taking away screen time if a child hits or giving a time-out if a learner begins throwing materials at their siblings.

Rules regarding punishment in ABA

Behavior Analysts have very strict rules about when and why to use punishment. For our earliest learners, punishment is only to be used after attempts at reinforcement have failed. An example would be we might offer a three-year-old a sticker for every five minutes they don’t throw hard objects. If this resolves the object-throwing behavior, there is no need for punishment. We would only consider punishment in this scenario because throwing hard objects can be dangerous to others in the child’s environment. For older learners, punishment might be used more hastily to quickly reduce dangerous behaviors—but always in conjunction with a reinforcement procedure. This could look like a 10-year-old getting a time out if he punches his brother but earning tokens to cash in for a larger prize for every 15 minutes, he has a safe body. In both cases, punishment is only being used because there is a present safety hazard.

Punishment, when implemented ethically and correctly, reduces dangerous behaviors in conjunction with reinforcement procedures. Historically, ABA providers have used punishment in other circumstances, such as to reduce stimming behaviors. As long as the stimming behavior does not present a danger or impediment to a child’s life, there is no need for the behavior to be reduced via punishment. Sometimes, stimming behaviors can be dangerous. For example, if a child is engaging in eye-stimming behavior while crossing the street, they may not see cars coming. An individual who likes to rub fabrics could get in real trouble if they start rubbing strangers on the street. Classic stimming behaviors like flapping or rocking may get in a learner’s way (it’s hard to learn to write or type when one is flapping), but this does not mean these behaviors need to be punished. Rather, finding appropriate times and places to engage in stimming behavior (changing when it happens as opposed to the fact that it does happen), is preferable to punishing something that a child clearly feels they need to do and is not harmful.

Evolving perspective on punishment in the field

This is a relatively new perspective for our field, and I am sure there are many neurodivergent individual today who were treated differently by ABA therapists in the past. Just like other fields, ABA is a constantly growing and evolving form of practice that constantly seeks to improve its ethical and practice standards. Similar to how the field of psychology has undergone similar evolutions from the ethical stumbles of the Zimbardo Prison Experiment, and The Milgram Shock Experiment, the field of ABA has been evolving since the days Ivar Lovaas tried to make children with ASD indistinguishable from their peers.

Ultimately, when ABA is being implemented properly, the impact of punishment is a reduction of the behavior that was being punished. Now, BCBAs may want to think long and hard about if and when punishment is going to be implemented. Providers may want to ask themselves, has my client or their parents expressly consented to this procedure? If not, the impact of the punishment may serve to reduce trust and faith with your client and their family, and our field overall.